News

Invisible No More

Play audio version

How the DJP Helped Me to Name and Embrace My Disability

February 18, 2022

BOSTON, United States of America — When my manic bipolar disorder manifested junior year of high school, it took some of my memories with it. Even now, staring at the ceiling of my room in the middle of the night, I squeeze my eyes shut as I attempt to piece the shattered fragments of my memories together. I often find myself wondering what echoes of my past are false or not, but I end up giving in and moving on because high school was a whirlpool that I barely pulled myself out of. Better to not reminisce too much or be reminded of the trigger that so lovingly invited my bipolar disorder to be a long-term guest in my rattled mind.

There are some things that I do remember, insignificant things during my first two years of high school. I was one of four freshman girls on the varsity soccer team before joining the marching band sophomore year. My sister, a titan of academia, graduated in the pouring rain before moving to New York City to attend New York University. I sang in three choirs, participated in the spring musical Bye Bye Birdie, and had a solo in show choir. As an active participant in my life during those years, those memories are vivid and tell the tale of a bright, happy young girl.

It ended. Junior year began. That bright, happy young girl couldn’t get out of bed.

I fought with my mother tirelessly, screamed and cried about going to school, started to fail my classes, and was out of school for roughly 73 days of my junior year. After an emergency room visit, I was diagnosed with major depression and anxiety. The bipolar diagnosis would come a year later. The word accommodation was floated around the room where I was forced to sit with my unforgiving high school principal and new guidance counselor. My principal begrudgingly accepted the recommendation of a late start time paired with the dropping of my pre-calculus class, but his eyes reminded me every day that I was a burden. I sometimes still see those eyes when an application asks me to disclose a disability.

Not once did anyone ever properly title why I was being given an accommodation – no one mentioned a disability. Because my disability was invisible, a psychosocial disability that couldn’t be seen with the naked eye, the last two years of my schooling were tortuous. It wasn’t enough that I cried every night and simultaneously bounced off the walls every day. To so many people, it wasn’t real, and it wasn’t a disability.

I received my diploma with all of my other classmates, on a sticky June day, seated on the turf football field that rarely saw any winning home games. When my principal handed me the diploma, he said, “I didn’t think you would make it.” A passing comment for him that ingrained itself into my mind, well into my adult life. I never visited the Accessibility Resources for Students office at Berklee College of Music to ask for accommodations. Instead, I quietly accepted the deduction in attendance points when I couldn’t drag myself to class. When I was called back to work after more than a year of lockdown and had a panic attack on the train because of the lack of social distancing, I never asked for a shift in work hours to accommodate the traffic, which would’ve probably been granted. I was still having trouble connecting bipolar disorder to psychosocial disability because no one had ever told me otherwise.

Fortunately, my concrete way of thinking started to rumble and crack as I accepted and furthered my role as communications/technical associate for the Disability Justice Project (DJP). My first assignment was to interview Esther Suubi, a fellow striving for recognition and resources for folks in Uganda with psychosocial disabilities. I remember opening the email with her information and furrowing my brow at the assignment requirements. A wave of confusion passed over me, unburying my long-held beliefs of disabilities. I was shocked to learn that psychosocial disabilities were considered for the DJP– not only considered but accepted. The little girl who suffered through high school, the same one that felt that she burdened others with her overlooked illness, started to heal that day. The healing and the unlearning started with meeting with Esther and hearing her story; it eagerly continued throughout the semester through interactions with other fellows.

Every week, the women of the DJP pushed me and my archaic ideas about disability to a whole new realm. Through the strength of these women and the unparalleled knowledge that they carry, I understand more. I understand that a disability can be more than what’s shown on the surface – some boil slightly underneath, warm to the touch. One disability does not trump the other, and no competition for ‘who has it worst?’ exists. Whether it’s DeafBlindess, spinal injuries, HIV/AIDS, depression, or other psychosocial disabilities, all are valid and deserve to be seen. I’m not sure I would have realized that without my work with the DJP. Moreover, I finally feel comfortable saying that my bipolar disorder is a disability, a term that eluded me for so long.

My old high school principal is retired now. I don’t spend much time, if any, wondering where he is. If I allow myself to wonder this one moment, I hope that he’s grown as I have and understands that disabilities are not always surface level. I hope that he and so many others who share his thoughts have learned that psychosocial disabilities are debilitating, discouraging, and so difficult, that they, too, deserve some attention and patience. I wish he could meet Esther, Rose, Oluwabukolami, Julie-Marie, and Nissy. Hopefully, their outstanding work will reach him as it’s already reached others. We’re all better off for it.

I still have moments where my memories fade in and out, but I know that this past semester will never leave me. It has filled the hole in my mind where all my old thoughts about what it means to have a disability used to frequent. I’m lucky, I’m informed, I’m empowered, I’m grateful. I’m thankful, thankful, thankful.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Voices Unsilenced

Often dismissed as a personal concern, mental health is a societal issue, according to Srijana KC, who works as a psychosocial counselor for the Nepali organization KOSHISH. KC’s own history includes a seizure disorder, which resulted in mental health challenges. She faced prejudice in both educational settings and the workplace, which pushed her towards becoming a street vendor to afford her medications. Now with KOSHISH, she coordinates peer support gatherings in different parts of Nepal. “It is crucial to instill hope in society, recognizing that individuals with psychosocial disabilities can significantly contribute,” she says.

Capturing Vision Through Sound and Touch

Last summer, the DJP trained Indigenous activists with disabilities from the Pacific on the iPhone camera to create a documentary series on disability and climate change. With VoiceOver, the iPhone provides image descriptions for blind and low-vision filmmakers and offers other accessible features. “If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense for a blind person to use a camera,” says DJP filmmaker Ari Hazelman. “The iPhone gives you more avenues to tell your story in a more profound way as a blind person.”

Beyond the Frame

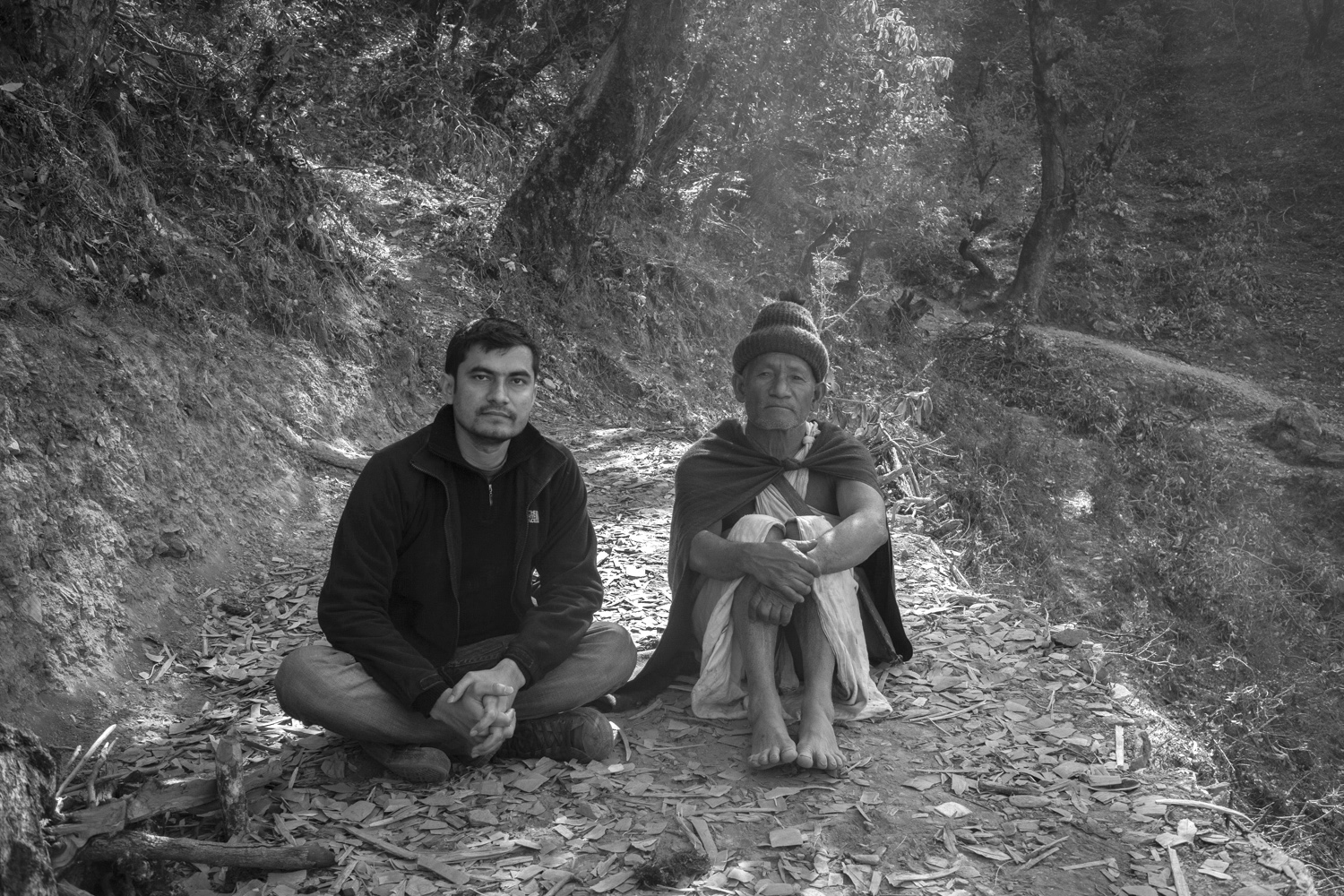

DJP mentor Kishor Sharma is known for his long-term photography and film projects exploring community and change. Over the last 12 years, he has been documenting the nomadic Raute people in mountainous Nepal. With any project, Sharma aims to actively engage participants, sharing photography and videography techniques. In September, Sharma became a mentor to DJP Fellow Chhitup Lama. He was eager to connect “this idea of sharing the visual technique with the storytelling idea and the issue of disability inclusion.”

‘I Am Left With Nothing’

Recent flooding in Rwanda has left many persons with disabilities without homes and jobs. “Sincerely speaking, I [am] left with nothing,” says Theophile Nzigiyimana, who considers himself lucky to have escaped the flooding. The flooding demonstrates the disproportionate impacts that disasters have on persons with disabilities, which will only intensify as climate change continues.

‘Leadership Training is a Key Focus’

DJP Fellow Sita Sah interviews Neera Adhikari about starting the Blind Women Association Nepal (BWAN) and the steps BWAN has taken to advance the rights of Nepali women who are blind and low-vision. Women with disabilities, particularly those living in rural areas, “face discrimination from family and society which prevents them from venturing outside their homes,” says Adhikari. “In a household where there are two children, one disabled son and one daughter, societal beliefs often favor sending the son to school while neglecting the daughter’s education.”

Accessible Instruction

Nepal has between 250,000 and one million Deaf people, but most do not attend school. In many schools for Deaf individuals, education ends at 10th grade, and higher education is rarely available and often inadequate. DJP Fellow Bishwamitra Bhitrakoti interviews Satya Devi Wagle from the National Federation of the Deaf Nepal about the strategies, challenges and successes of her work on inclusive education. “Because hearing teachers are not competent in sign language, there is no quality instruction in a resource class in Nepal,” she says. “We are working … to create a Deaf-friendly curriculum.”