News

Beyond the Frame

Play audio version

DJP Mentor Kishor Sharma Forges a Collaborative Path in Visual Storytelling

January 8, 2024

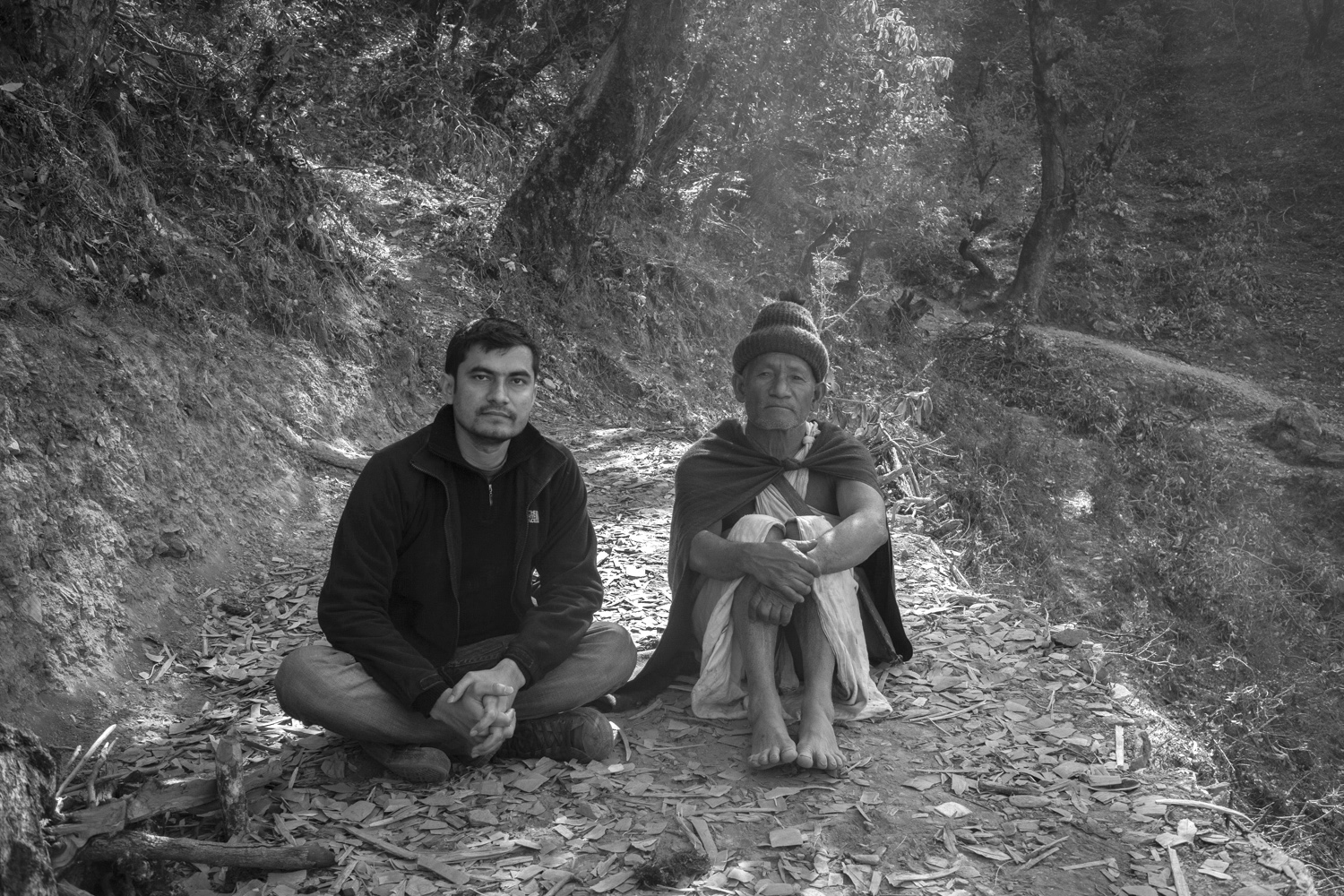

KATHMANDU, Nepal – Kishor Sharma’s photography and film work spans a wide range of subjects and locations across Nepal and South Asia. He has done traditional photojournalism work for publications such as Time Magazine, The Guardian, and Nepali Times. But, perhaps Sharma’s most compelling work is his longer-term photography and film projects, which investigate questions of communities and change. One of these projects is Sharma’s documentation of the nomadic Raute people of mountainous Nepal, which has been finalized into a photography book called Living in the Mist, published this year. The black-and-white images of Sharma’s book paint a vivid – and visually moving – portrait of a small Indigenous community whose nomadic lifestyle conflicts with the modern world. Sharma’s work with the Raute community – with whom he has spent a great deal of time since beginning his research in 2011 – has largely been a passion project. Without formal funding initially, Sharma’s work continued for years “out of my own interest,” he says. The result is a photographic immersion that feels both mythological and culturally honest.

Sharma’s visual work – which also includes filmmaking – creates moments of deeper reflection in an era of instantly shared images on social media. “I’m a bit old school, I think. I like projects where I could just spend some time and then sort of build a project,” he says. In addition to Living in the Mist, Sharma has been producing a series of short films and videos for the environmental organization KTK-BELT, which promotes Indigenous knowledge of the natural world. These short pieces highlight local natural guides and farmers who share their perspectives on natural life and how it interacts with their own lives. Sharma considers his subjects “farmer-professors.” “There’s like the importance of the academic expertise but also the expertise of the living experience,” he says.

Collaboration and Mutual Participation

Beyond merely keeping focus on the Indigenous perspective, Sharma aims to “share the photography or videography technique with the participant.” It’s a “collaborative sort of project,” he says. Collaboration and mutual participation between photographer/director and subject seems to be a central theme of Sharma’s career. Sharma has a bachelor’s degree in business from Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, a master’s in mass communication from Purbanchal University, and he received a diploma in photojournalism in 2014 from the Danish School of Media and Journalism. Sharma has been teaching photography to students and the public continuously ever since completing his degrees. Through university classes and workshops, he hopes to enrich photography and film education in Nepal, which was much less robust during his youth. Beyond bringing visual media education to Nepal as a whole, he has found particular value in bringing it to marginalized communities, such as persons with disabilities.

Sharma was recently introduced to Jody Santos, executive director of the Disability Justice Project (DJP). He was inspired by the filmmaking and disability-focused mission of the DJP and eager to connect “this idea of sharing the visual technique with the storytelling idea and the issue of disability inclusion.” Sharma was assigned to work as a mentor to one of the DJP’s new fellows from Nepal — Chhitup Lama.

Lama leads HEAD Nepal, a disability inclusion organization based in the country’s Himalayan region. HEAD Nepal has been supporting Nepalis with disabilities since 2011. Lama has been the subject of several films already, and Sharma remembers Lama remarking, “Now I want to be behind the camera.” After being accepted as a DJP fellow, Lama was enthralled browsing through previous fellows’ work. He felt inspired by the term “disability-inclusive filmmaking.” With a touch of whimsy, Lama remembers thinking, “Why not me? Even [though] I cannot see, let’s make a film!”

Teaching the Technical Skills of Filmmaking

Both Sharma and Lama are from rural regions of Nepal. Sharma grew up in the lowland Bara district (although he moved to Kathmandu at age 10), and Lama is from the mountainous Humla district in mid-western Nepal. Lama faced significant challenges going to school in the 1990s, both in terms of physical and societal obstacles. He recalls how the landscape he grew up in was beautiful yet “almost completely inaccessible” to those with disabilities given the geography and lack of transportation. In school, Lama wasn’t able to see the blackboards or access the lesson books. He had to learn by listening to his teachers’ lectures and then commit the lessons to memory. Lama went on to earn degrees in social entrepreneurship from the Kanthari International Institute India and an M.A. in English literature from Tribhuvan University. Reflecting on his educational success, he says, “one of the beautiful parts of life so far, what I learned is I love, you know, difficulties, challenging problems.”

Since 2011, Lama has run and expanded HEAD Nepal, which now offers educational, vocational, and counseling services to both children and adults with disabilities. Informed by his own path, Lama emphasizes respect for people’s dignity: “When we work with a person with a disability, we see them with their rights,” he says. HEAD Nepal takes a “bottom-up approach” where “the community… are the key stakeholders.”

This focus on doing work with the consent and active participation of community members is perhaps what bonds Sharma and Lama in their work with the DJP. With these mutual goals in the background, their relationship so far has focused on the technical skills of filmmaking. With several online training sessions under their belt (and plans to meet in person soon), Sharma has been teaching Lama filming and interviewing techniques and visual image concepts. For the fellowship, Lama will complete a number of video assignments, culminating in a short documentary film.

There are some real challenges to the mentorship, both acknowledge. Because of his disability, Lama says it can be difficult “to focus the camera and sometimes to zoom in and zoom out.” But, these are welcome challenges as he seeks to mix up his work at HEAD Nepal: “I want to do something different, and that gives me some energy. That gives me some fun and … of course, happiness.” With new skills under his belt, Lama hopes to integrate more photography and filmmaking projects into his leadership work at HEAD Nepal. Sharma, for his part, is eager to both teach and learn from Lama as they continue their partnership.

Sam Norton is a writer and video editor who lives in the USA between New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Rwanda’s Marburg Crisis

As Rwanda confronts its first-ever Marburg virus outbreak, people with disabilities face heightened risks — not only from the virus but also from the lack of accessible health information. “Without proper accommodations, such as sign language interpreters, captions, Braille, or visual aids, the Deaf and DeafBlind community may miss crucial information about how to protect themselves, symptoms to watch for, or where to seek help in case of infection,” says Joseph Musabyimana, executive director of the Rwanda Organization of Persons with Deaf Blindness.

Capturing Vision Through Sound and Touch

Last summer, the DJP trained Indigenous activists with disabilities from the Pacific on the iPhone camera to create a documentary series on disability and climate change. With VoiceOver, the iPhone provides image descriptions for blind and low-vision filmmakers and offers other accessible features. “If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense for a blind person to use a camera,” says DJP filmmaker Ari Hazelman. “The iPhone gives you more avenues to tell your story in a more profound way as a blind person.”

Work for All

The We Can Work program equips young Rwandans with disabilities to navigate barriers to employment through education, vocational training, and soft skills development. By fostering inclusive workplaces and advocating for policy changes, the program aims to reduce poverty and promote economic independence. Participants like Alliance Ukwishaka are optimistic that the program will enable them to achieve their dreams and showcase their potential. The initiative is part of a larger effort to support 30 million disabled youth across seven African countries.

Global Recognition

Faaolo Utumapu-Utailesolo’s film “Dramatic Waves of Change” has been named a finalist in the Focus on Ability International Short Film Festival. The film, completed during a Disability Justice Project workshop in Samoa, highlights the impact of climate change on people with disabilities in Kiribati. Utumapu-Utailesolo, who is blind, used an iPhone with accessibility features to create the film. “Do not leave people with disabilities behind when [you] plan, implement, and monitor programs regarding climate change and disaster,” she says. Her achievement is a testament to the power of inclusive filmmaking.

Advancing Democracy

Rwanda has made significant progress in making its elections more accessible, highlighted by the July 15 general elections where notable accommodations were provided. This was a major step forward in disabled Rwandans’ quest for equal rights and participation. “You cannot imagine how happy I am, for I have voted by myself and privately as others do accessibly,” says Jean Marie Vianney Mukeshimana, who used a Braille voting slate for the first time. “Voting is a deeply emotional and meaningful experience for a person with any disability in Rwanda, reflecting a blend of pride, empowerment, and hope.”

Barriers to the Ballot

Despite legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act, barriers at the polls still hinder — and often prevent — people with disabilities from voting. New restrictive laws in some states, such as criminalizing assistance with voting, exacerbate these issues. Advocacy groups continue to fight for improved accessibility and increased voter turnout among disabled individuals, emphasizing the need for multiple voting options to accommodate diverse needs. ““Of course, we want to vote,” says Claire Stanley with the American Council of the Blind, “but if you can’t, you can’t.”