News

More Than A Name

Play audio version

‘Being a woman, coming from a working-class family, and living with a psychosocial disability means I am a triply marginalized identity.’

February 15, 2023

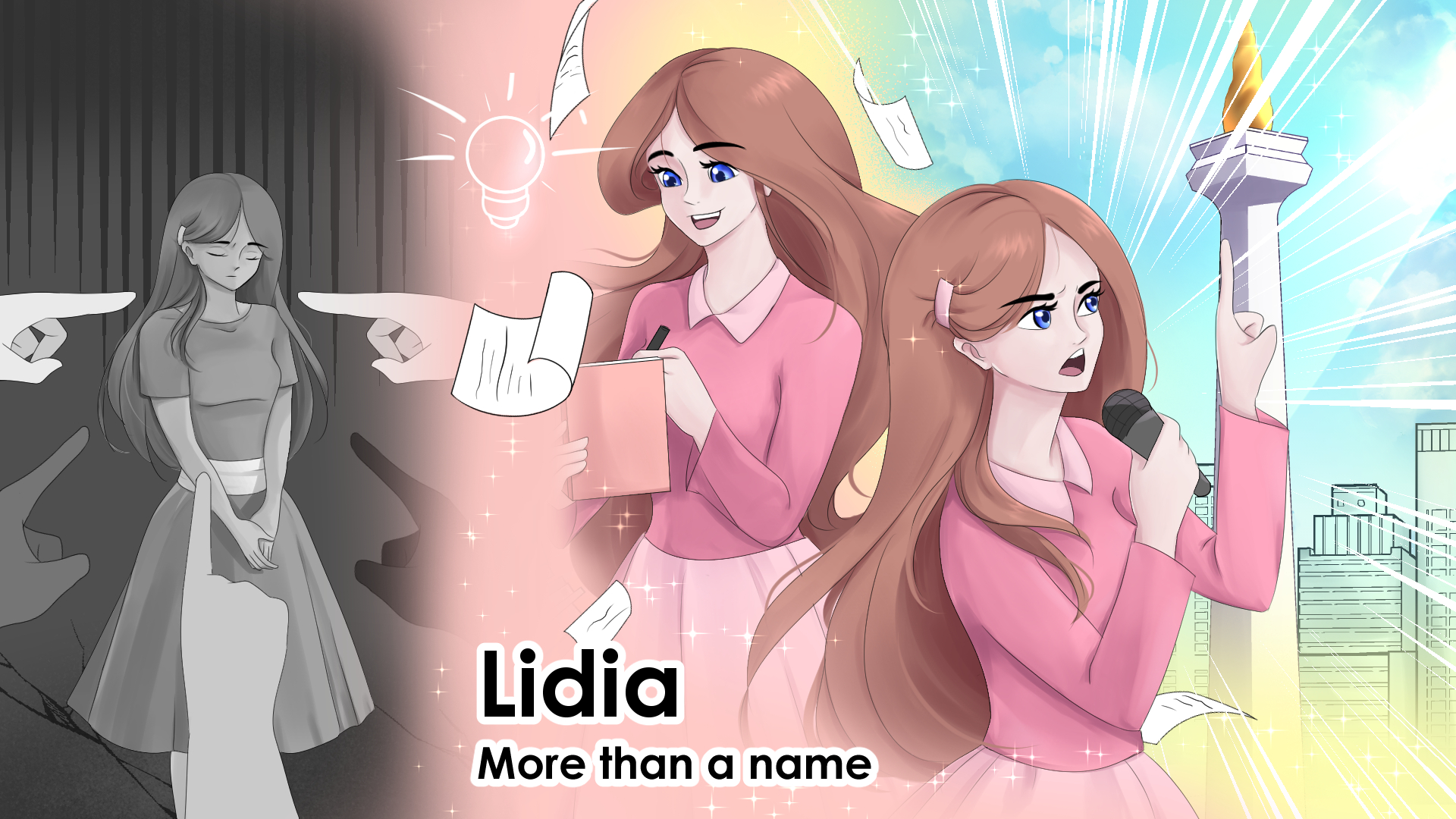

Naming has become a rite of passage throughout human history. My parents named me Lidia, a name taken from the Bible, hoping I would mirror the hospitality of Lidia, a merchant from Thyatira who once opened her home to the Apostle Paul and some of his companions in the Roman city of Philippi.

Until my teenage years, before I really began to think about my identity, mentioning my name was the only thing I could do when people asked me who I was. After graduating high school, I left my hometown of Toraja, South Sulawesi, for Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, to attend college. Moving from my homogeneous habitat to the most diverse area in Indonesia, I became aware that I was so much more than just Lidia. I was a girl with an accent from a working-class family who had to crawl in order to thrive.

I was led to become more than hospitable. I had to labor. Laboring – as hard as it may sound – can be even more difficult when you are anxious about disadvantages like a lack of money. But my determination and my efforts were as wide as the Grand Canyon. I got a scholarship to the United States. The initial plan was to finish a master’s program in pastoral counseling within three years; it was a clinical track program. After one year, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a psychosocial disability that causes episodes of depression and mania.

My bipolar was so severe that I fell into a psychosis – a break from reality. In the hospital, the nurses took samples of my blood and urine and ran some tests to see if there were other medical conditions contributing to my illness. “There’s nothing wrong, only vitamin D deficiency,” said the psychiatrist. “A lack of vitamin D could affect one’s mood.” Bipolar disorder is often referred to as a mood disorder, though I learned in my healing process that it’s so much more than that. The doctor prescribed a high dose of vitamin D along with other medicines. Never in my life did I think that I would need to consult a doctor about taking vitamin D. Where I come from, I did not have such privilege.

At this point, I imagine you could identify which group(s) I belong to. I am a woman – a gender often seen in Indonesia’s patriarchal society as a second, or inferior, gender. I come from a working-class family. I live with bipolar disorder, which makes me a person with a disability. These are parts of my identity that make me who I am now. Being a woman, coming from a working-class family, and living with a psychosocial disability means I am a triply marginalized identity. My chances for equal work opportunities are limited. The lack of employment opportunities for Indonesians with psychosocial disabilities has been documented by organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) like the Indonesian Mental Health Association (IMHA). IMHA often points out how the Indonesian government systematically and structurally discriminates against people with psychosocial disabilities. This discrimination takes the form of what is called “surat keterangan sehat rohani,” or a certificate of spiritual (read: mental) health. This certificate is one of the requirements to apply for a job. The certificate must be issued by a psychiatrist.

My chance to be accepted in a romantic relationship is limited as well. When people learn about my disability, I can see in their faces how surprised they are – how they believe they are facing a person who is less than them, someone not capable of having a family. But again, my determination, spirit, and efforts are vast, so I found a way to heal from this through writing.

A youth-led organization called YIFoS hired me as their book consultant. They want me to interview participants who have been changed by their program, which has three key themes: equality, tolerance, and inclusion. I carry my work well, no less than persons without disabilities. More important, I am able to work well as part of a team. Performing well in my work is a way for me to advocate for myself and other people with disabilities.

When injustices bubble to the surface, I no longer act in a way that society perceives as hospitable. In my neighborhood, people used to make fun of me, saying I was a crazy person living in the area. I told them that a person with disabilities is protected by law and that if they continued, I would call the National Commission on Human Rights. I have learned that one must advocate and be willing to be assertive and vocal, even though in a patriarchal society, these qualities are associated more with men. But again, I am more than my gender and name, and I will not be defined by others.

Lidia Lebang is a mental health advocate with bipolar and anxiety disorders. She has a passion for the intersection of spirituality, psychology/mental health, and activism. She has written three books in Indonesian, and she is currently working on her first book in English, titled The Extended Self: A Diary of An Asian Woman Living with Mental Illnesses.@2023 Lidia Lebang. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Advancing Democracy

Rwanda has made significant progress in making its elections more accessible, highlighted by the July 15 general elections where notable accommodations were provided. This was a major step forward in disabled Rwandans’ quest for equal rights and participation. “You cannot imagine how happy I am, for I have voted by myself and privately as others do accessibly,” says Jean Marie Vianney Mukeshimana, who used a Braille voting slate for the first time. “Voting is a deeply emotional and meaningful experience for a person with any disability in Rwanda, reflecting a blend of pride, empowerment, and hope.”

Barriers to the Ballot

Despite legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act, barriers at the polls still hinder — and often prevent — people with disabilities from voting. New restrictive laws in some states, such as criminalizing assistance with voting, exacerbate these issues. Advocacy groups continue to fight for improved accessibility and increased voter turnout among disabled individuals, emphasizing the need for multiple voting options to accommodate diverse needs. ““Of course, we want to vote,” says Claire Stanley with the American Council of the Blind, “but if you can’t, you can’t.”

Democracy Denied

In 2024, a record number of voters worldwide will head to the polls, but many disabled individuals still face significant barriers. In India, inaccessible electronic voting machines and polling stations hinder the ability of disabled voters to cast their ballots independently. Despite legal protections and efforts to improve accessibility, systemic issues continue to prevent many from fully participating in the world’s largest democracy. “All across India, the perception of having made a place accessible,” says Vaishnavi Jayakumar of Disability Rights Alliance, “is to put a decent ramp at the entrance and some form of quasi-accessible toilet.”

Triumph Over Despair

DJP Fellow Esther Suubi shares her journey of finding purpose in supporting others with psychosocial disabilities. She explores the transformative power of peer support and her evolution to becoming an advocate for mental health. “Whenever I see people back on their feet and thriving, they encourage me to continue supporting others so that I don’t leave anyone behind,” she says. “It is a process that is sometimes challenging, but it also helps me to learn, unlearn, and relearn new ways that I can support someone – and myself.”

‘Our Vote Matters’

As Rwanda prepares for its presidential elections, voices like Daniel Mushimiyimana’s have a powerful message: every vote counts, including those of citizens with disabilities. Despite legal frameworks like the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, challenges persist in translating these into practical, accessible voting experiences for over 446,453 Rwandans with disabilities. To cast a vote, blind people need to take a sighted relative to read the ballot. An electoral committee member must be present, violating the blind person’s voting privacy. “We want that to change in these coming elections,” says Mushimiyimana.

Voices Unsilenced

Often dismissed as a personal concern, mental health is a societal issue, according to Srijana KC, who works as a psychosocial counselor for the Nepali organization KOSHISH. KC’s own history includes a seizure disorder, which resulted in mental health challenges. She faced prejudice in both educational settings and the workplace, which pushed her towards becoming a street vendor to afford her medications. Now with KOSHISH, she coordinates peer support gatherings in different parts of Nepal. “It is crucial to instill hope in society, recognizing that individuals with psychosocial disabilities can significantly contribute,” she says.