News

Right to Access Social Assistance

Play audio version

Indonesian Social Assistance Policy Ignores the Existence of Individuals with Psychosocial Disabilities

August 2, 2022

Translated from Bahasa Indonesia.

Click here for the Bahasa Indonesia version of this article.

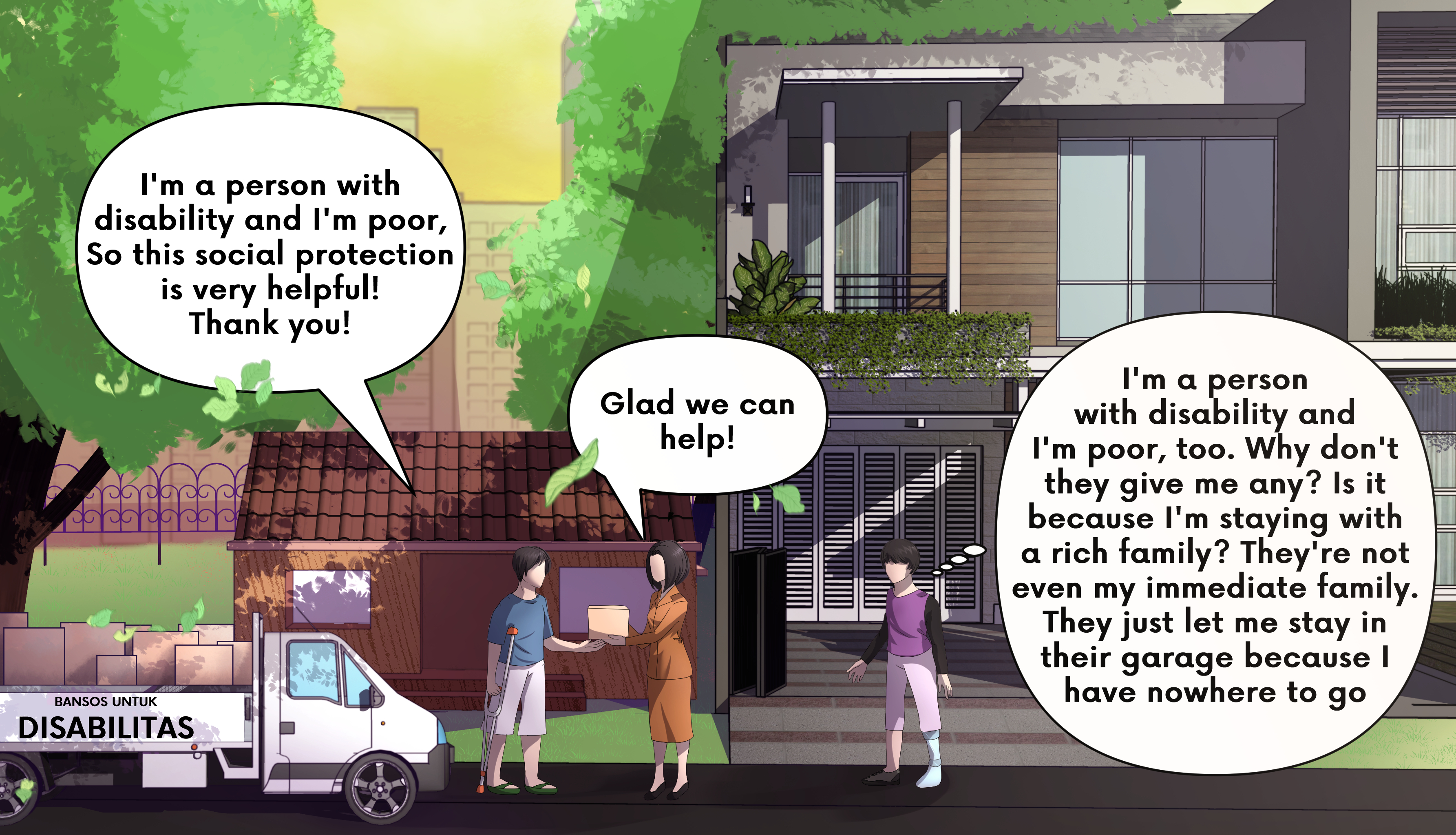

JAKARTA, Indonesia — “Bambang,” an Indonesian Mental Health Association (IMHA) member with schizophrenia who wishes to remain anonymous, faces a dilemma. He is unemployed, but because he lives with his mother and sister in a house on the edge of a major road in Jakarta, he is ineligible for public social assistance. While Bambang doesn’t work and has no income of his own, his eligibility for social assistance is based on his family’s income, not his own. Because his mother and sister live in a larger house in a wealthier part of town, they are considered too “rich” for him to qualify for assistance. This leaves Bambang dependent on others for his survival. If he lives with his family, he is denied social assistance; if he doesn’t live with his family, he will become homeless.

According to Yeni Rosa Damayanti, chairperson of IMHA (also known as Perhimpunan Jiwa Sehat), many Indonesians with disabilities are forced to live with family members – cousins, aunts, parents – in garages and in other less than ideal housing situations. Damayanti says government social protection schemes are usually based on the family, not the individual. To receive social assistance from the Indonesian government, a citizen undergoes the Integrated Social Welfare Management (DTKS) process. Registrants must not own property, a car, or live in a “rich” area, among other criteria. Since Bambang’s family home is valued at over 66,000 U.S. dollars, he is ineligible for government support. Such criteria deny assistance to many persons with disabilities.

The Right to Live Independently

Indonesian Law No. 8 of 2016 Article 17 guarantees the “right to social welfare for Persons with Disabilities [including] social rehabilitation, social insurance, social empowerment, and social protection,” and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) Article 19 recognizes the right of persons with disabilities to choose where they live with no obligation “to live in a particular living arrangement.” Overall, persons with disabilities have the right to live on their own – to not be dependent on anyone for their survival – but Indonesia’s social assistance policies make this all but impossible.

A 2020 survey led by the Disabled People’s Organization (DPO) Network for a More Inclusive Covid Response found that while 9 percent of Indonesians have a disability, only 3 percent receive regular social protection benefits. In a report accompanying the survey, the authors note that the voices of persons with disabilities are often missing in policymaking – even though this is a requirement of the UNCRPD.

Inaccessible Application Process

Adding to the problem is the fact that the DTKS website page is inaccessible; its performance is slow because millions of Jakarta inhabitants are accessing the website at the same time and because it shares servers with other ministries. DTKS registrants only have 30 days to sign up once the government announces registration re-opening periods. As a result of the website’s slow performance compounded by Jakarta’s population size, many people like Bambang do not have enough time to register before the deadline. During his registration period in February, Bambang tried to access the website multiple times until he gave up and finally registered with the help of a local government official.

First built in 2015, the Ministry of Social Affairs DTKS system includes data on Social Welfare Service Recipients (PPKS) for programs like the Family Home Program (PKH), Basic Food Assistance, and the Jakarta Persons with Disabilities Card (KPDJ), the latter of which Bambang sought but was denied. Today, he is left to make ends meet. He finds it difficult to find a job and seeks assistance from organizations of persons with disabilities like IMHA. “I don’t get cash assistance at all … I only get social assistance channeled through organizations,” Bambang says. He is not the only IMHA member facing this issue. Other IMHA members have been forced to live with families that the government does not recognize as poor enough to receive assistance.

Data collection inconsistencies in Indonesia add fuel to the flame. “The government must be more serious in taking care of this disability problem, starting from comprehensive and thorough data collection … There must be a reliable data unit that is used to distribute assistance that is the right of disability,” says Bambang. A study by the National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction (TNP2K) notes that access to social protection, one of the various rights persons with disabilities have without discrimination, tends to be limited for various reasons. These include limited data information related to disability in Indonesia. Such limited information reduces the urgency for the government to prioritize and allocate resources to persons with disabilities.

The study mentions persons with disability face challenges in accessing different birth certificates, too. A 2014 study conducted by a partnership between the Indonesian and Australian governments for programs endorsing the values of justice (AIPJ) found that inaccessible offices and “complicated procedures” make it hard for persons with disabilities to apply for and receive legal identity documents. Another 2017 study reveals that the main reason Indonesian children (with or without disabilities) do not have birth certificates, a required document to access services, is cost. Many parents also don’t realize the need for such a document – and that they are entitled to these public services. Although the TNP2K and Australian Government study says the Indonesian government has taken steps to increase access to birth certificates for all children, inaccessible government documents exacerbate the challenges persons with disabilities face when attempting to register for social assistance.

Bambang remains hopeful he will receive social assistance in the future: “I really deserve [the Jakarta Persons with Disabilities Card] KPDJ because I am a disabled person who requires more money.”

Kinanty Andini is a 2022 DJP fellow and affiliate with the Indonesian Mental Health Association (IMHA) also known as Perhimpunan Jiwa Sehat. @2022 Indonesian Mental Health Association (Perhimpunan Jiwa Sehat). All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

‘Everything Has Gone Back’

Before Myanmar’s 2021 military coup, disability advocates were helping shape national policy for the first time in decades. Laws expanded access to education, transportation, and public life. Today, much of that progress has collapsed. A new UN report describes a “hidden crisis,” documenting targeted violence, deadly attacks, and the exclusion of people with disabilities from warnings, aid, and services. As conflict creates new disabilities and organizations are forced underground, advocates work quietly to preserve rights that once seemed within reach.

‘I Just Want to Walk Alone’

Fourteen-year-old Saifi Qudra relies on others to move safely through his day. Like many blind children in Rwanda, he has never had a white cane. His father, Mussah Habineza, escorts him everywhere. “He wants to walk like other children,” Habineza says, “He wants to be free.” Across Rwanda, the absence of white canes limits children’s mobility, confidence, and opportunity. For families, it also shapes daily routines, futures, and the boundaries of independence.

‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

As climate change and conflict intensify across Pakistan, emergency systems continue to exclude people with disabilities. Warning messages, evacuation routes, and shelters are often inaccessible, leaving many without critical information when floods or violence erupt. “Evacuation routes are built for people who can run,” Deaf author and policy advocate Kashaf Alvi says, “and information is broadcast in ways that a significant population cannot access.”

Read more about ‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

Autism, Reframed

Late in life, Malaysian filmmaker Beatrice Leong learned she was autistic and began reckoning with decades of misdiagnosis, harm, and erasure. What started as interviews with other late-diagnosed women became a decision to tell her own story, on her own terms. In The Myth of Monsters, Leong reframes autism through lived experience, using filmmaking as an act of self-definition and political refusal.

Disability and Due Process

As Indonesia overhauls its criminal code, disability rights advocates say long-standing barriers are being reinforced rather than removed. Nena Hutahaean, a lawyer and activist, warns the new code treats disability through a charitable lens rather than as a matter of rights. “Persons with disabilities aren’t supported to be independent and empowered,” she says. “… They’re considered incapable.”

Disability in a Time of War

Ukraine’s long-standing system of institutionalizing children with disabilities has only worsened under the pressures of war. While some facilities received funding to rebuild, children with the highest support needs were left in overcrowded, understaffed institutions where neglect deepened as the conflict escalated. “The war brought incredibly immediate, visceral dangers for this population,” says DRI’s Eric Rosenthal. “Once the war hit, they were immediately left behind.”