News

Rule of Law

Play audio version

Disability Rights Activist Ariani Soekanwo Uses Indonesian Laws to Achieve Inclusion Across Every Sector of Society

July 7, 2022

Translated from Bahasa Indonesia.

Click here for the Bahasa Indonesia version of this article.

YOGYAKARTA, Indonesia — Even though she can’t see the traffic lights clearly, Ariani Soekanwo rides her motorcycle on Yogyakarta’s crowded highways. “Well, I just follow the people around me; if they all stop, it means the light is red and I stop, too,” she says.

Ariani Soekanwo has had low vision since childhood due to retinitis pigmentosa, a rare inherited degenerative eye disease. Born in 1945 in Yogyakarta, a city in Java, Indonesia, she developed her own ways to engage with the world around her. “I could still play hide-and-seek with my friends, even though sometimes my friends didn’t really hide because they thought I couldn’t recognize them from afar,” she says. “I used my other senses to recognize them, such as my sense of smell and hearing. I can recognize my friends by their smells and the sound of their footsteps.”

Now at the age of 76, Soekanwo has created a lasting legacy as a disability rights activist in Indonesia, advocating for other persons with disabilities to be able to fully engage in every aspect of society. Over the years, she has helped start several disability rights organizations in her country, each of which has had a significant impact on everything from inclusive elections to accessible infrastructure.

Starting when she was still in college, Soekanwo and some friends founded Pertuni (Indonesian Blind Union) in 1966. Over the next decade, as she helped run the organization, she noticed a concerning trend. At most meetings, Soekanwo was the only woman with a disability in the room. At the time, many Indonesian women, particularly those with disabilities, were still confined to their homes – denied the opportunity to participate in society fully. In 1997, with the support of the Indonesian National Council for Social Welfare, Soekanwo and several other women with disabilities started what is now called the Association of Indonesian Women with Disabilities (HWDI). Today, HWDI is a national powerhouse, with branches in over 30 provinces. Among its advocacy efforts, HWDI has been a strong proponent of changing an article in Indonesia’s marriage law that allows husbands to divorce their wives if their wives become permanently disabled.

Civic Participation as the Lifeblood of Democracy

Recognizing civic participation as the lifeblood of any democracy, Soekanwo eventually turned her attention to ensuring the rights of persons with disabilities to vote (through accessible polling places and practices) and to run for office. Up until the late 1990s in Indonesia, persons with disabilities were barred from running for parliament. Three seemingly innocuous articles in the election law were responsible for this. One required that candidates be of “sound mental and physical health,” which was initially interpreted to exclude persons with disabilities. The second insisted candidates be able to read and write Roman letters, which ruled out people who were blind. The last article said legislative candidates must be able to speak and write in Indonesian, which shut out people with speech disabilities.

The situation was no better for voters with disabilities. Inaccessible voting places – narrow doorways, no ramps – resulted in voter participation rates among persons with disabilities substantially lower than the rest of the population. In one survey by The Asia Foundation, just over half of Indonesians with disabilities surveyed said they’d voted in the 2009 parliamentary elections, and 65.4 percent said they’d voted in the previous presidential election. This was over 10 percent less than official participation rates for the general population.

To address these concerns, Soekanwo and several of her colleagues from other national disability organizations formed PPUA Disability (the Center for Election Access of Citizens with Disabilities). They began to inventory several election regulations that did not support persons with disabilities. Their efforts have begun to bear fruit. From 2004 until now, there has been a significant increase among voters with disabilities participating in general elections – even among voters with psychosocial disabilities who previously were considered legally incompetent to vote.

Reversing Discriminatory Election Policies

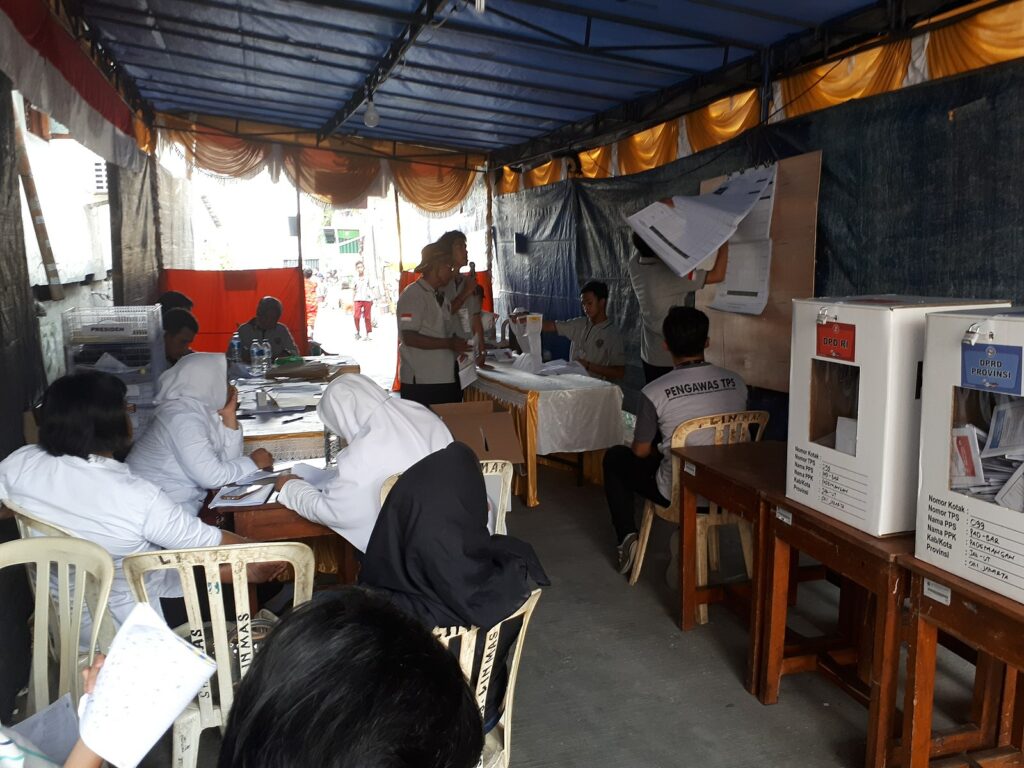

Thanks to the efforts of PPUA and other groups, Indonesia passed “Electoral Code, Law No. 7” which reversed many of its discriminatory election policies. For instance, Article 240 of the law says, “Requirements in this provision shall not limit the political rights of a citizen with a disability who [is] able to perform their tasks and responsibilities.” Article 350 mandates that polling stations be “easily accessible by able-bodied voters as well as voters with disabilities.” With this law in place, more polling stations throughout Indonesia today are providing Braille ballot templates for blind voters and lower ballot boxes for wheelchair users. Election officials are also allowing voters with disabilities to bring companions to the polls if they need to. On the candidate side, people with disabilities from every province ran for office during the last election.

To date, PPUA has been established in almost 34 provinces across Indonesia, and Soekanwo continues to push for disability rights across all sectors of society. Age is not an obstacle for her. Her enthusiasm for encouraging the fulfillment of rights for persons with disabilities in Indonesia pushes her to never stop thinking and creating. Even after forming PPUA, she initiated the formation of several other organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs). These included the National Public Accessibility Movement, which focuses on auditing public facilities and infrastructure to make sure they are accessible and offer inclusive services, and Permata Disability, which provides assistance to children with disabilities from low-income families.

The presence of OPDs like these has brought changes to almost every corner of the country. Soekanwo realizes Indonesia still has a long way to go in achieving full inclusion for persons with disabilities, but one step at a time – one organization at a time – she and her colleagues are working toward that goal.

Mahretta Maha is a 2022 DJP Fellow and a program officer with PPUA Disability. @2022 PPUA. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Capturing Vision Through Sound and Touch

Last summer, the DJP trained Indigenous activists with disabilities from the Pacific on the iPhone camera to create a documentary series on disability and climate change. With VoiceOver, the iPhone provides image descriptions for blind and low-vision filmmakers and offers other accessible features. “If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense for a blind person to use a camera,” says DJP filmmaker Ari Hazelman. “The iPhone gives you more avenues to tell your story in a more profound way as a blind person.”

Work for All

The We Can Work program equips young Rwandans with disabilities to navigate barriers to employment through education, vocational training, and soft skills development. By fostering inclusive workplaces and advocating for policy changes, the program aims to reduce poverty and promote economic independence. Participants like Alliance Ukwishaka are optimistic that the program will enable them to achieve their dreams and showcase their potential. The initiative is part of a larger effort to support 30 million disabled youth across seven African countries.

Global Recognition

Faaolo Utumapu-Utailesolo’s film “Dramatic Waves of Change” has been named a finalist in the Focus on Ability International Short Film Festival. The film, completed during a Disability Justice Project workshop in Samoa, highlights the impact of climate change on people with disabilities in Kiribati. Utumapu-Utailesolo, who is blind, used an iPhone with accessibility features to create the film. “Do not leave people with disabilities behind when [you] plan, implement, and monitor programs regarding climate change and disaster,” she says. Her achievement is a testament to the power of inclusive filmmaking.

Advancing Democracy

Rwanda has made significant progress in making its elections more accessible, highlighted by the July 15 general elections where notable accommodations were provided. This was a major step forward in disabled Rwandans’ quest for equal rights and participation. “You cannot imagine how happy I am, for I have voted by myself and privately as others do accessibly,” says Jean Marie Vianney Mukeshimana, who used a Braille voting slate for the first time. “Voting is a deeply emotional and meaningful experience for a person with any disability in Rwanda, reflecting a blend of pride, empowerment, and hope.”

Barriers to the Ballot

Despite legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act, barriers at the polls still hinder — and often prevent — people with disabilities from voting. New restrictive laws in some states, such as criminalizing assistance with voting, exacerbate these issues. Advocacy groups continue to fight for improved accessibility and increased voter turnout among disabled individuals, emphasizing the need for multiple voting options to accommodate diverse needs. ““Of course, we want to vote,” says Claire Stanley with the American Council of the Blind, “but if you can’t, you can’t.”

Democracy Denied

In 2024, a record number of voters worldwide will head to the polls, but many disabled individuals still face significant barriers. In India, inaccessible electronic voting machines and polling stations hinder the ability of disabled voters to cast their ballots independently. Despite legal protections and efforts to improve accessibility, systemic issues continue to prevent many from fully participating in the world’s largest democracy. “All across India, the perception of having made a place accessible,” says Vaishnavi Jayakumar of Disability Rights Alliance, “is to put a decent ramp at the entrance and some form of quasi-accessible toilet.”