News

The Language Gap

Rwanda’s Sign Language Dictionary Sparked Hope, But Without Cabinet Recognition, Frustration Is Growing.

November 2, 2025

KIGALI, Rwanda — More than a year after the official launch of the Rwandan Sign Language Dictionary, Deaf communities across the country are still waiting for what they consider the most crucial step – formal recognition by Rwanda’s Cabinet.

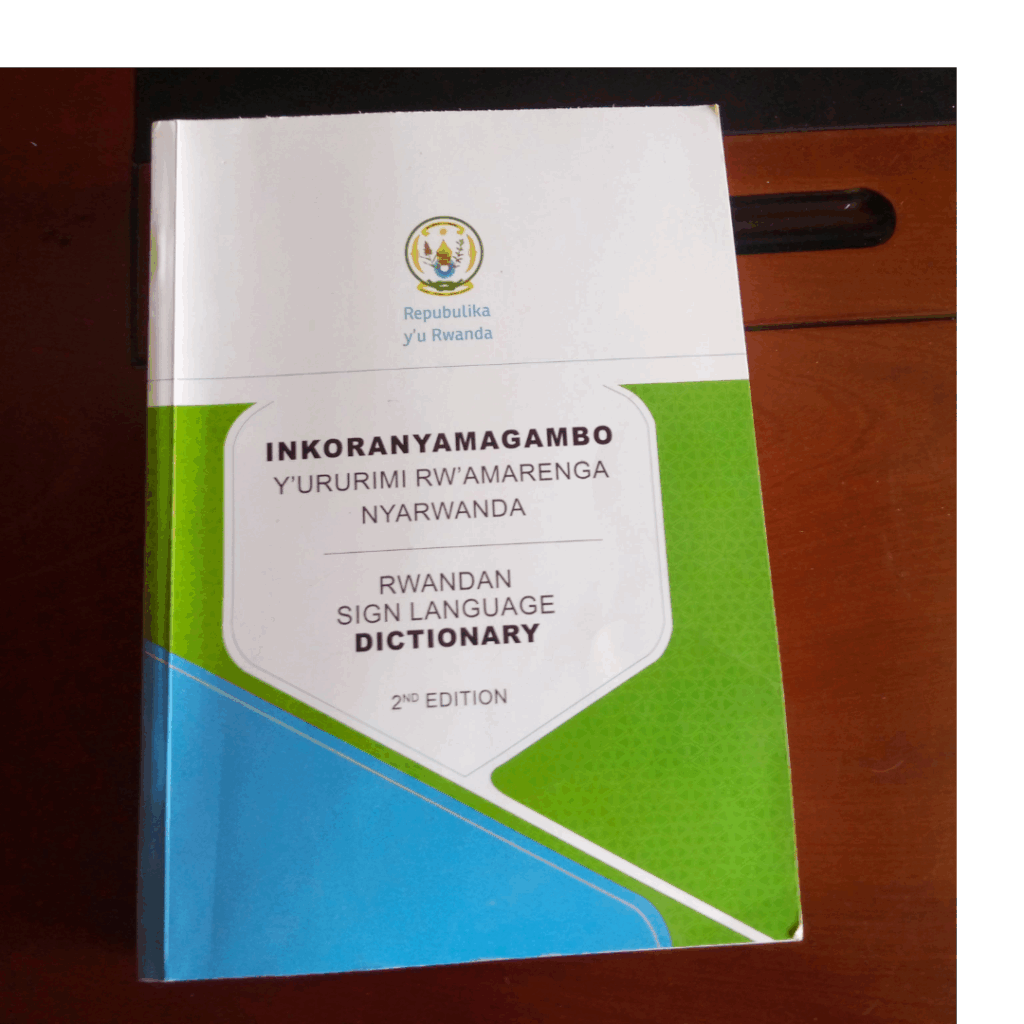

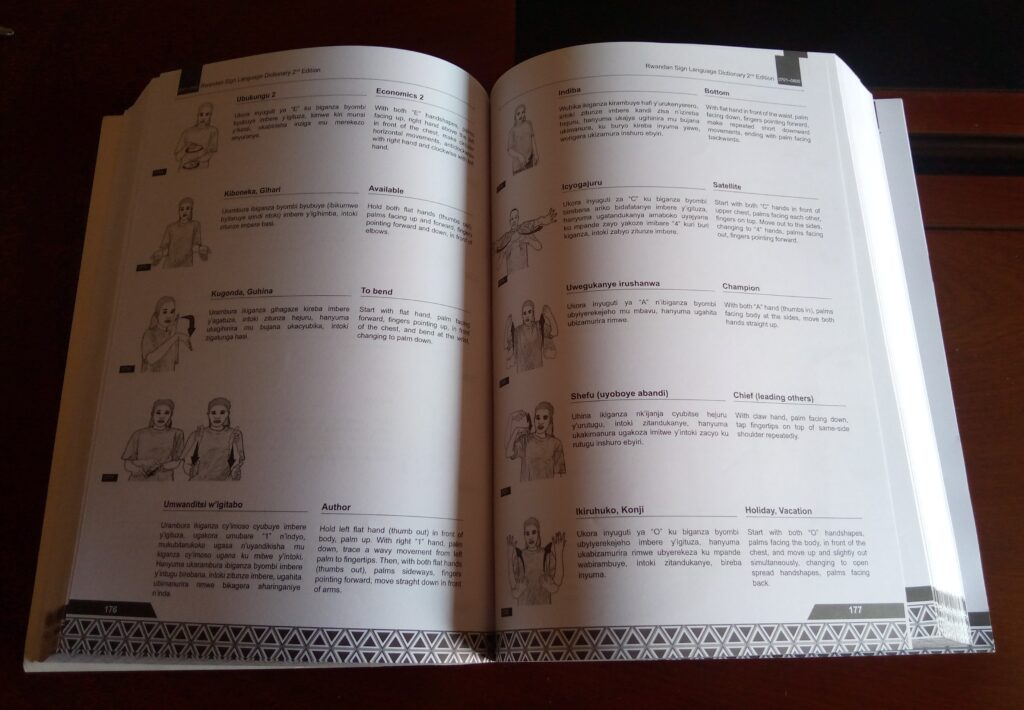

Completed in 2022 after years of consultation, the dictionary was launched publicly on December 14, 2023, and distribution began nationwide in 2024. It was celebrated as a milestone for linguistic rights, accessibility, and Deaf inclusion.

Yet despite its circulation, the dictionary remains without Cabinet approval and, therefore, without legal force. The lack of official recognition means there is still no standardized sign language in Rwanda’s schools, hospitals, or courts. Teachers and interpreters rely on inconsistent regional signs, making communication unreliable. Deaf students may struggle to follow lessons, and patients risk serious misunderstandings in medical settings. For many, the promise of inclusion remains only partially realized.

“This is not just a book of signs. It is our voice,” says Allan Mutabazi, executive director of Rwanda National Union of the Deaf. “But until the Cabinet approves it, our voice is still being silenced by the system.” Mutabazi’s organization worked on the dictionary in partnership with the National Council of Persons with Disabilities.

Without Cabinet approval, institutions can choose whether or not to adopt the standardized signs. For many Deaf Rwandans, that means communication in daily life still relies on guesswork. “In the hospital, we still write down symptoms or point to pictures,” says Jannat Umuhoza, a Deaf woman in Kigali. “If doctors used sign language from the dictionary, I would feel safe and understood.”

According to the Rwanda National Union of the Deaf and the 2022 Population Census, more than 42,000 Deaf and hard-of-hearing Rwandans stand to benefit from the dictionary’s formal recognition. The community is growing increasingly impatient and worried that the momentum from 2023’s launch may be fading. “We were told it’s a big achievement, and it is. But it must be backed by law,” Umuhoza emphasizes. “Otherwise, it’s a tool without power.”

Ongoing Struggle for Visibility

For many members of the Deaf community, the delay feels like part of a broader issue: the invisibility of sign language users in national decision-making. “The problem is not just recognition of the dictionary, it’s recognition of us,” says Kevine Niyokwizerwa, a Deaf youth advocate in Kigali. “We are Rwandans. We contribute to society. Our language deserves the same respect as Kinyarwanda, English, and French.”

The National Policy on Disability states that accessibility in communication is a non-negotiable right for persons with disabilities. Similarly, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Rwanda is a signatory, affirms the right to language and communication for persons with disabilities. Article 21 in particular commits Rwanda to accept and facilitate the use of sign languages and recognize and promote the use of sign languages. Yet without the Cabinet’s approval of the new dictionary, advocates say these rights remain theoretical for many Deaf citizens because there is no official standard for teaching, interpreting, and providing public services in sign language.

“We need more than symbolic gestures,” says Claudine Murekatete, a Deaf mother of two from Rubavu. “We need policies that protect our children’s future.”

Murekatete adds that the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child also makes it clear that States are required to ensure that children with disabilities have access to information and communication in a manner appropriate to their needs: “For us, Deaf children remain disadvantaged in school if teachers and learning materials do not use a recognized form of Rwandan Sign Language,” she says.

Serious Consequences

Mutabazi says the delay in approving the Rwandan Sign Language Dictionary also has serious consequences for access to justice. Court interpreters are left without a standard legal sign vocabulary, increasing the risk of misinterpretations that could lead to unfair rulings or miscarriages of justice. For Deaf individuals, this means their testimonies, rights, and legal standing may be compromised simply because there is no agreed-upon language standard to ensure accurate and consistent communication in legal proceedings.

In healthcare, without a standardized sign language reference, explaining symptoms, diagnoses, and treatment plans will remain inconsistent, increasing the risk of misunderstandings that could harm patient outcomes. This communication gap not only undermines the right to health but also deepens the existing inequalities in access to quality care for Deaf Rwandans.

The delay also affects opportunities for work and participation in community life. Without a standardized communication system, many employers hesitate to recruit Deaf staff, reinforcing barriers to inclusion. Socially, the lack of recognition sends the message that sign language is an optional accommodation rather than a fundamental right. This keeps Deaf people on the margins of public life and national dialogue.

A Call to the Cabinet

Mutabazi and other advocates are now renewing their call for Cabinet action. Their goal is that, by the end of 2025, the Rwandan Sign Language Dictionary will be recognized as a national linguistic tool, complete with legal and institutional responsibilities for its use and implementation.

In their proposal submitted to the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Local Government earlier this year, they requested that the dictionary be officially recognized, printed in larger quantities, distributed to schools and health centers, and used to train teachers and interpreters nationwide.

They also called for a broader Sign language policy that would outline interpreter accreditation, inclusion in teacher training colleges, and budget allocations for Deaf communication support. “We are not asking for charity. We are demanding inclusion,” says Mutabazi.

As Rwanda makes strides toward inclusive development and universal access to public services, the Deaf community insists that language access must be treated as a right, not an afterthought.

Recognizing the Rwandan Sign Language Dictionary as a cornerstone of inclusion and accessibility, Emmanuel Ndayisaba, executive secretary of National Council of Persons with Disabilities, says the Council is working closely with relevant ministries, including the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Local Government, Ministry of Justice, the Rwanda Law Reform Commission, and other related institutions, to ensure the dictionary’s official approval. “Every partner involved in this initiative is committed to making it a success, especially the Ministry of Education, which plans to begin using the dictionary in schools,” he says.

On the other hand, a government official at the Rwanda Heritage Academy, speaking anonymously, confirmed that discussions on the dictionary’s recognition are ongoing and that recommendations from the Deaf community are being reviewed.

Ndayisaba says the community remains patient and determined, as the Ministry of Education and NCPD, with the support of the Deaf community, have already developed supporting materials for the dictionary and trained some teachers and parents of Deaf children on how to use it. “We are currently drafting a law, which we hope to finalize very soon and present to the responsible ministries before submitting it to the Cabinet,” he says. “We are doing our best to ensure its approval. We understand that recognizing a new language is not an easy process, but we are hopeful that it will be achieved next year.”

As the wait for official approval continues, Mutabazi delivers a heartfelt reminder of what is at stake for the Deaf community: “Every day without recognition is a day someone is left behind. But we won’t stop fighting. This is our language. This is our right, and there is no human right without sign language.”

Francine Uwayisaba is a field officer at the Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP), in charge of the organization’s communications. She writes grants, manages RULP’s social media, and composes articles and weekly updates for its website.

Editing assistance by Jody Santos

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

‘I Just Want to Walk Alone’

Fourteen-year-old Saifi Qudra relies on others to move safely through his day. Like many blind children in Rwanda, he has never had a white cane. His father, Mussah Habineza, escorts him everywhere. “He wants to walk like other children,” Habineza says, “He wants to be free.” Across Rwanda, the absence of white canes limits children’s mobility, confidence, and opportunity. For families, it also shapes daily routines, futures, and the boundaries of independence.

‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

As climate change and conflict intensify across Pakistan, emergency systems continue to exclude people with disabilities. Warning messages, evacuation routes, and shelters are often inaccessible, leaving many without critical information when floods or violence erupt. “Evacuation routes are built for people who can run,” Deaf author and policy advocate Kashaf Alvi says, “and information is broadcast in ways that a significant population cannot access.”

Read more about ‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

Autism, Reframed

Late in life, Malaysian filmmaker Beatrice Leong learned she was autistic and began reckoning with decades of misdiagnosis, harm, and erasure. What started as interviews with other late-diagnosed women became a decision to tell her own story, on her own terms. In The Myth of Monsters, Leong reframes autism through lived experience, using filmmaking as an act of self-definition and political refusal.

Disability and Due Process

As Indonesia overhauls its criminal code, disability rights advocates say long-standing barriers are being reinforced rather than removed. Nena Hutahaean, a lawyer and activist, warns the new code treats disability through a charitable lens rather than as a matter of rights. “Persons with disabilities aren’t supported to be independent and empowered,” she says. “… They’re considered incapable.”

Disability in a Time of War

Ukraine’s long-standing system of institutionalizing children with disabilities has only worsened under the pressures of war. While some facilities received funding to rebuild, children with the highest support needs were left in overcrowded, understaffed institutions where neglect deepened as the conflict escalated. “The war brought incredibly immediate, visceral dangers for this population,” says DRI’s Eric Rosenthal. “Once the war hit, they were immediately left behind.”

The Language Gap

More than a year after the launch of Rwanda’s Sign Language Dictionary, Deaf communities are still waiting for the government to make it official. Without Cabinet recognition, communication in classrooms, hospitals, and courts remains inconsistent. “In the hospital, we still write down symptoms or point to pictures,” says Jannat Umuhoza. “If doctors used sign language from the dictionary, I would feel safe and understood.”