News

Toward Equitable Health Care

Play audio version

Rwandans with Short Stature Advocate for More Accessible Services, From Lower Reception Windows and Beds to Better Communication

December 14, 2022

KIGALI, Rwanda — Persons with disabilities experience significant barriers to accessing health care, including inaccessible medical clinics and hospitals, a lack of accessible transport options, untrained personnel, inadequate staffing, stigma and discrimination, and inaccessible communication methods and materials. These barriers can be particularly challenging for those residing in rural areas.

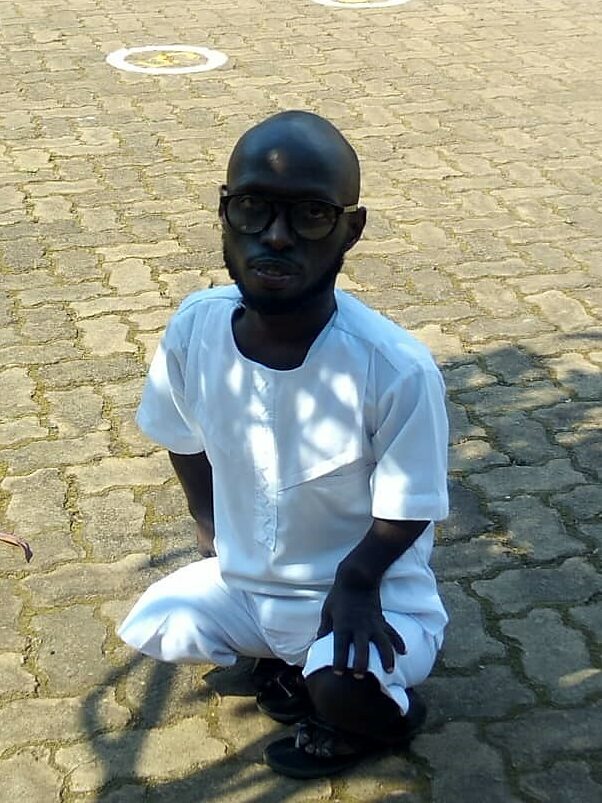

Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP) recently conducted an accessibility visit to one local and one regional health center to check on how persons with short stature (also known as persons with dwarfism or little people) could or could not access healthcare services.

“As we know, any person needs healthcare services for any reason, but to persons with short stature, it seems like they are not expected to need such services, as they never access materials and even buildings where they use stairs,” says Appoline Buntubwimana, legal representative at RULP, “and when you ask, they tell you that they never thought of persons with that type of disability. It is rarely finding any post-health center, health center, or even a hospital whose buildings and materials are accessible to persons with short stature in Rwanda.”

During RULP’s visit, staff examined the room where women give birth, checking whether it was accessible for a woman with short stature. Health center officials acknowledged the beds are not accessible – that they are for all women and not specifically for women with short stature. As a result, medical personnel must lift up patients with short stature onto the beds. It is the only way they’ll receive medical attention.

Theodole Niyigaba is a man with short stature who lives in Kigali. He says accessible health services for Rwandans with short stature are nonexistent. Service windows and beds are too high, and patients often must climb steep stairs to access services. “From the introduction of COVID-19 in Rwanda, I have never used any public handwashing station due to their standards. Moreover, in case I need hospital services, like taking medicine, I entered the office instead of waiting at the windows because no one can see me.”

Leonidas Batamugira, director of Remera Health Centre in Kigali, says that although the Rwandan government is trying to help persons with disabilities access services, when it comes to how buildings are constructed and furnished inside, they are still inaccessible to persons with short stature. “Generally, the available chairs, delivery beds, stairs, handwashing facilities, in-patient beds, doors, general chair and tables, we really know that they are not accessible to persons with short stature. Truly, it needs an extra budget that we do not have to have such materials, so we lift her/him up, or else we transfer them to the district hospital for special help,” he says.

Historically, persons with short stature are one of the most marginalized groups in Rwanda. Many have been rejected by their families or bullied by peers, leading to self-isolation and stigma. They have been denied an education, leading to a lack of knowledge about various health conditions and the right people to see when a problem arises. When it comes to healthcare services, they meet physical, material, and communication barriers.

Buntubwimana says persons with short stature are seriously struggling with accessing health care, from reception areas to where they should be receiving services to even who is providing such services. “Many health services like reception, paying for services, and where to take medicine, services are provided through windows which are tall,” she says. “Everyone may imagine what happens when no one is around to help him or her to ask for such services. Sometimes we are served after others or choose to stay home.”

Francine Uwayisaba is a field officer at Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP) and in charge of the organization’s communications. She writes grants, manages RULP’s social media, and composes articles and weekly updates for the website. @2022 RULP. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Advancing Democracy

Rwanda has made significant progress in making its elections more accessible, highlighted by the July 15 general elections where notable accommodations were provided. This was a major step forward in disabled Rwandans’ quest for equal rights and participation. “You cannot imagine how happy I am, for I have voted by myself and privately as others do accessibly,” says Jean Marie Vianney Mukeshimana, who used a Braille voting slate for the first time. “Voting is a deeply emotional and meaningful experience for a person with any disability in Rwanda, reflecting a blend of pride, empowerment, and hope.”

Barriers to the Ballot

Despite legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act, barriers at the polls still hinder — and often prevent — people with disabilities from voting. New restrictive laws in some states, such as criminalizing assistance with voting, exacerbate these issues. Advocacy groups continue to fight for improved accessibility and increased voter turnout among disabled individuals, emphasizing the need for multiple voting options to accommodate diverse needs. ““Of course, we want to vote,” says Claire Stanley with the American Council of the Blind, “but if you can’t, you can’t.”

Democracy Denied

In 2024, a record number of voters worldwide will head to the polls, but many disabled individuals still face significant barriers. In India, inaccessible electronic voting machines and polling stations hinder the ability of disabled voters to cast their ballots independently. Despite legal protections and efforts to improve accessibility, systemic issues continue to prevent many from fully participating in the world’s largest democracy. “All across India, the perception of having made a place accessible,” says Vaishnavi Jayakumar of Disability Rights Alliance, “is to put a decent ramp at the entrance and some form of quasi-accessible toilet.”

Triumph Over Despair

DJP Fellow Esther Suubi shares her journey of finding purpose in supporting others with psychosocial disabilities. She explores the transformative power of peer support and her evolution to becoming an advocate for mental health. “Whenever I see people back on their feet and thriving, they encourage me to continue supporting others so that I don’t leave anyone behind,” she says. “It is a process that is sometimes challenging, but it also helps me to learn, unlearn, and relearn new ways that I can support someone – and myself.”

‘Our Vote Matters’

As Rwanda prepares for its presidential elections, voices like Daniel Mushimiyimana’s have a powerful message: every vote counts, including those of citizens with disabilities. Despite legal frameworks like the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, challenges persist in translating these into practical, accessible voting experiences for over 446,453 Rwandans with disabilities. To cast a vote, blind people need to take a sighted relative to read the ballot. An electoral committee member must be present, violating the blind person’s voting privacy. “We want that to change in these coming elections,” says Mushimiyimana.

Voices Unsilenced

Often dismissed as a personal concern, mental health is a societal issue, according to Srijana KC, who works as a psychosocial counselor for the Nepali organization KOSHISH. KC’s own history includes a seizure disorder, which resulted in mental health challenges. She faced prejudice in both educational settings and the workplace, which pushed her towards becoming a street vendor to afford her medications. Now with KOSHISH, she coordinates peer support gatherings in different parts of Nepal. “It is crucial to instill hope in society, recognizing that individuals with psychosocial disabilities can significantly contribute,” she says.