News

‘Videos Are Like Art to Me’

When she was four years old, DJP Fellow Kinanty Andini drew all over the walls of her mother’s house. Now she’s using her creativity to make films that fight against mental health stigmas.

November 7, 2022

JAKARTA, Indonesia – During her 2022 fellowship with the Disability Justice Project, Kinanty Andini decided to make a film about workplace discrimination against Indonesian workers with psychosocial disabilities. While she focused her video on two women who were fired after their employers found out about their mental health conditions, the inspiration behind the story was Andini’s own lived experience.

“I had a job two years ago. … I hid the fact that I had psychosocial issues,” says Andini. “And I experienced it too – that my employer found out that I’m a person with a psychosocial disability. And they fired me.”

As a child, Andini was passionate about art. She even had a habit of drawing all over the walls of her family’s home in Indonesia.

“I used to make the walls of my house into a giant canvas,” says Andini. “Thankfully, my mother never scolded me for ruining her beautiful house. Instead, she gave me a lot of papers, drawing books, and a box of pencils. She said, ‘It’s okay to be creative, but you have to be creative in the right way.’”

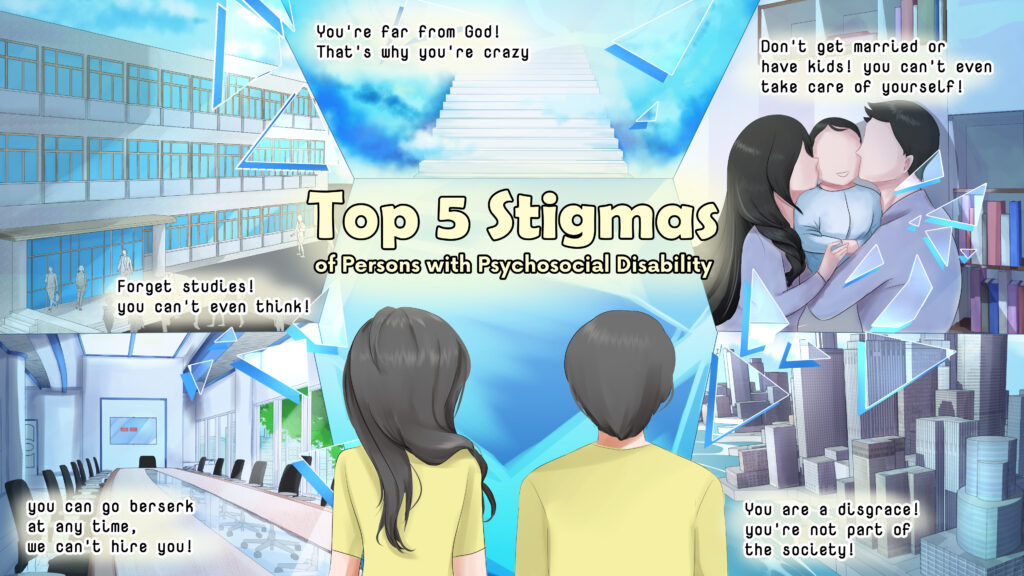

During her fellowship with the DJP, Andini has been channeling her love for visual art into making films about disability rights issues. One of the problems she wants to address most is the stigmatization of mental health conditions.

“The issue I focus on the most is stigma,” says Andini, “or you can call it labels for people with psychosocial disabilities that are created by society. Because most of the discrimination against us is based on those stigmas.”

According to Andini, the consequences of being stigmatized are serious in Indonesia. She says people with psychosocial disabilities experience everything from bullying in school and workplace discrimination to “pasung.” Currently banned in Indonesia, pasung is the practice of restraining individuals who have psychosocial disabilities using shackles. According to Andini, along with reports by Human Rights Watch and other organizations, it’s still widely used across the country today.

Pasung is just one topic that Andini is thinking about addressing in the future through her videos and visual art. She says the ultimate goal of her work is to show society who people with psychosocial disabilities are – beyond the stigmas attached to their condition.

“The world should get rid of any negative stigma against us from their minds,” says Kinanty, “and begin to see us as humans. Yes, the same human beings like them. We have feelings. We can think. We can work, too.”

Delainey LaHood-Burns is a digital content producer based in New Hampshire and a contributor to the Disability Justice Project. @2022 Disability Justice Project. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

‘I Just Want to Walk Alone’

Fourteen-year-old Saifi Qudra relies on others to move safely through his day. Like many blind children in Rwanda, he has never had a white cane. His father, Mussah Habineza, escorts him everywhere. “He wants to walk like other children,” Habineza says, “He wants to be free.” Across Rwanda, the absence of white canes limits children’s mobility, confidence, and opportunity. For families, it also shapes daily routines, futures, and the boundaries of independence.

‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

As climate change and conflict intensify across Pakistan, emergency systems continue to exclude people with disabilities. Warning messages, evacuation routes, and shelters are often inaccessible, leaving many without critical information when floods or violence erupt. “Evacuation routes are built for people who can run,” Deaf author and policy advocate Kashaf Alvi says, “and information is broadcast in ways that a significant population cannot access.”

Read more about ‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

Autism, Reframed

Late in life, Malaysian filmmaker Beatrice Leong learned she was autistic and began reckoning with decades of misdiagnosis, harm, and erasure. What started as interviews with other late-diagnosed women became a decision to tell her own story, on her own terms. In The Myth of Monsters, Leong reframes autism through lived experience, using filmmaking as an act of self-definition and political refusal.

Disability and Due Process

As Indonesia overhauls its criminal code, disability rights advocates say long-standing barriers are being reinforced rather than removed. Nena Hutahaean, a lawyer and activist, warns the new code treats disability through a charitable lens rather than as a matter of rights. “Persons with disabilities aren’t supported to be independent and empowered,” she says. “… They’re considered incapable.”

Disability in a Time of War

Ukraine’s long-standing system of institutionalizing children with disabilities has only worsened under the pressures of war. While some facilities received funding to rebuild, children with the highest support needs were left in overcrowded, understaffed institutions where neglect deepened as the conflict escalated. “The war brought incredibly immediate, visceral dangers for this population,” says DRI’s Eric Rosenthal. “Once the war hit, they were immediately left behind.”

The Language Gap

More than a year after the launch of Rwanda’s Sign Language Dictionary, Deaf communities are still waiting for the government to make it official. Without Cabinet recognition, communication in classrooms, hospitals, and courts remains inconsistent. “In the hospital, we still write down symptoms or point to pictures,” says Jannat Umuhoza. “If doctors used sign language from the dictionary, I would feel safe and understood.”