News

Advancing Democracy

Play audio version

Historic Voting Accessibility for Rwandans with Disabilities

July 18, 2023

This is the fourth article in our series on accessible elections across the globe.

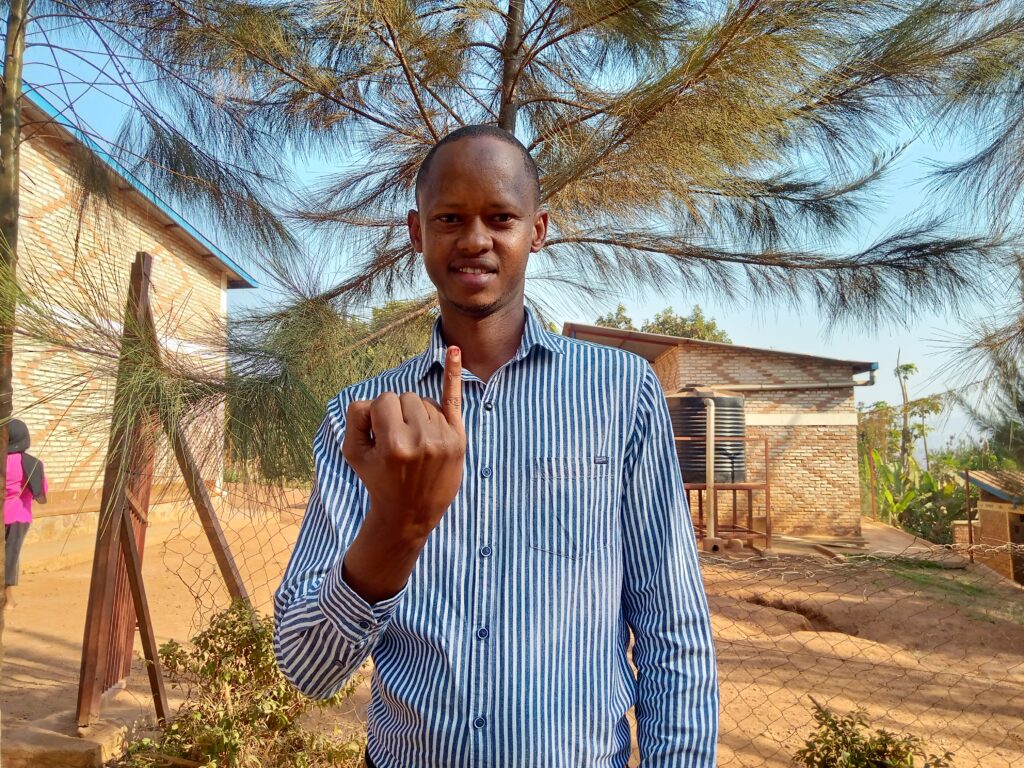

KIGALI, Rwanda – Rwanda has been making strides in ensuring its elections are accessible to all its citizens, including those with disabilities. In its general elections on July 15, Rwandans with disabilities noted significant improvements to accommodations, marking a notable shift toward greater inclusion and equality in the democratic process.

Voting is a cornerstone of democracy, allowing citizens to exercise their civic duty and influence their country’s governance. For Rwandans with disabilities, the recent presidential and parliamentary elections were a step forward in their quest for equal rights and participation.

“Voting can be a powerful and emotional experience for anyone, but for a person with a disability in Rwanda, the emotions can be particularly profound due to our background related to voting,” says Jean Marie Vianney Mukeshimana, who is blind.

With great emotion, Mukeshimana mentions how, in all his years voting, he has never experienced such accessible elections as those on July 15. For the first time, Mukeshimana used a Braille voting slate, which allowed him to vote privately and independently. In previous years, he’d relied on a child to vote for him. “You cannot imagine how happy I am, for I have voted by myself and privately as others do accessibly,” he says. “Voting is a deeply emotional and meaningful experience for a person with any disability in Rwanda, reflecting a blend of pride, empowerment, and hope.”

Chemsa Iradukunda shares how happy she was to have a voice as a person with a psychosocial disability in the decision-making process that affects her community and country. “Rwandan law related to voting used to exclude us [persons with psychosocial disabilities] from voting, saying that we may cause troubles to the voting sites. But today, I am so happy, for I voted who I want to lead our country and hope will help in the well-being of persons with disabilities. I’m really thankful for the advocacy done to make this election more accessible to persons with disability, particularly with psychosocial. From the time I reached the polling place, they immediately helped me to enter, without any [worry] that I may cause troubles.”

However, not all experiences on July 15 were positive. Jean Damascene Bizimana, a Deaf voter, highlights the ongoing challenges for the Deaf community due to the lack of sign language interpreters at polling sites. “We still encounter a number of challenges while voting as persons who are Deaf. Reaching the polling place, others are welcomed and being explained everything [they are] going to do, but our only issue is that we need a sign language interpreter to understand what they are saying, where to go, and how everyone is going to vote. You can stay at the polling place from morning until the time they finish voting due to poor communication at the polling place. I think we are forgotten that we will vote as other citizens do.”

Olive Nakure, a woman with DeafBlindness, also faced significant barriers due to the absence of trained interpreters familiar with tactile sign language. “Reaching the polling station, none knew that I can neither see nor hear or speak as well. I entered and find where to sit while waiting for my personal assistant to come and help me reach a voting room,” she says. “I imagined how I was going to know all related to voting, thinking that they have an interpreter but they did not think of it. For sure, it is something to be sad about, and I wish next time, they will bring a tactile interpreter or plan any other way we may vote. If electronic voting machines had been used, It would have been more helpful to us.”

Physical accessibility remains a challenge for wheelchair users and persons with short stature. Marie Aime Dukuzem, a wheelchair user, struggled with the voting booth’s small doors, while David Gacamumakuba, a person of short stature, found the standard height of voting booths difficult to use. “From the main gate to the voting room, everything has been fine. They welcome you with happiness, asking your village to show your voting room without making you line up as a person with disability,” says Dukuzem. “[However], I did not get a chance to enter the voting booth due to using a wheelchair, which [forced] me to vote out of the booth, and [that violates] personal privacy. As a wheelchair user, I am happy that I have at least voted by myself, and I am sure that my voice is valuable and it is my responsibility as a Rwandan to participate in the appointment of leaders who will lead us.”

Gacamumakuba voted for the second time in his life on July 15. He says physical inaccessibility, like the lack of adjustable-height voting booths, continues to be a barrier for persons with short stature. However, compared to previous years, this election was improved. For instance, polling staff managed to remove stairs wherever possible. “I am pleased to find myself to the voting list and to vote for my choice. This is a positive experience that generates feelings of empowerment, knowing that my voice matters and that I have contributed to shaping the future of my community and country as well,” he says. “I really hope that I made a good choice, that my vote will help all persons with disabilities to reach their full accessibility. Overall, we shall once vote accessibly, though it may not be today, but there is hope for continued progress.”

“Voting is a fundamental right, and being able to exercise it without encountering barriers is incredibly affirming,” adds Emmanuel Ndayisaba, executive secretary of the National Council of Persons with Disabilities (NCPD Rwanda). While acknowledging the significant improvements in recent elections, he recognizes the need for more sign language and tactile interpreters. He says he will continue to advocate for more accessible elections in the future through the Disability Management Information System (DMIS) being developed by NCPD.

While there is still work to be done, the recent elections in Rwanda represent a significant step toward greater accessibility and inclusion for persons with disabilities. These improvements are a testament to the ongoing efforts to ensure that every Rwandan can participate fully in the democratic process.

Francine Uwayisaba is a contributing writer with the Disability Justice Project and a field officer at Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP). At RULP, she is in charge of the organization’s communications. She writes grants, manages RULP’s social media, and composes articles and weekly updates for the website. @2024 DJP. All rights reserved.

Editing assistance by Jody Santos

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

‘I Just Want to Walk Alone’

Fourteen-year-old Saifi Qudra relies on others to move safely through his day. Like many blind children in Rwanda, he has never had a white cane. His father, Mussah Habineza, escorts him everywhere. “He wants to walk like other children,” Habineza says, “He wants to be free.” Across Rwanda, the absence of white canes limits children’s mobility, confidence, and opportunity. For families, it also shapes daily routines, futures, and the boundaries of independence.

‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

As climate change and conflict intensify across Pakistan, emergency systems continue to exclude people with disabilities. Warning messages, evacuation routes, and shelters are often inaccessible, leaving many without critical information when floods or violence erupt. “Evacuation routes are built for people who can run,” Deaf author and policy advocate Kashaf Alvi says, “and information is broadcast in ways that a significant population cannot access.”

Read more about ‘Evacuation Routes Are Meant for People Who Can Run’

Autism, Reframed

Late in life, Malaysian filmmaker Beatrice Leong learned she was autistic and began reckoning with decades of misdiagnosis, harm, and erasure. What started as interviews with other late-diagnosed women became a decision to tell her own story, on her own terms. In The Myth of Monsters, Leong reframes autism through lived experience, using filmmaking as an act of self-definition and political refusal.

Disability and Due Process

As Indonesia overhauls its criminal code, disability rights advocates say long-standing barriers are being reinforced rather than removed. Nena Hutahaean, a lawyer and activist, warns the new code treats disability through a charitable lens rather than as a matter of rights. “Persons with disabilities aren’t supported to be independent and empowered,” she says. “… They’re considered incapable.”

Disability in a Time of War

Ukraine’s long-standing system of institutionalizing children with disabilities has only worsened under the pressures of war. While some facilities received funding to rebuild, children with the highest support needs were left in overcrowded, understaffed institutions where neglect deepened as the conflict escalated. “The war brought incredibly immediate, visceral dangers for this population,” says DRI’s Eric Rosenthal. “Once the war hit, they were immediately left behind.”

The Language Gap

More than a year after the launch of Rwanda’s Sign Language Dictionary, Deaf communities are still waiting for the government to make it official. Without Cabinet recognition, communication in classrooms, hospitals, and courts remains inconsistent. “In the hospital, we still write down symptoms or point to pictures,” says Jannat Umuhoza. “If doctors used sign language from the dictionary, I would feel safe and understood.”