News

More Than A Name

Play audio version

‘Being a woman, coming from a working-class family, and living with a psychosocial disability means I am a triply marginalized identity.’

February 15, 2023

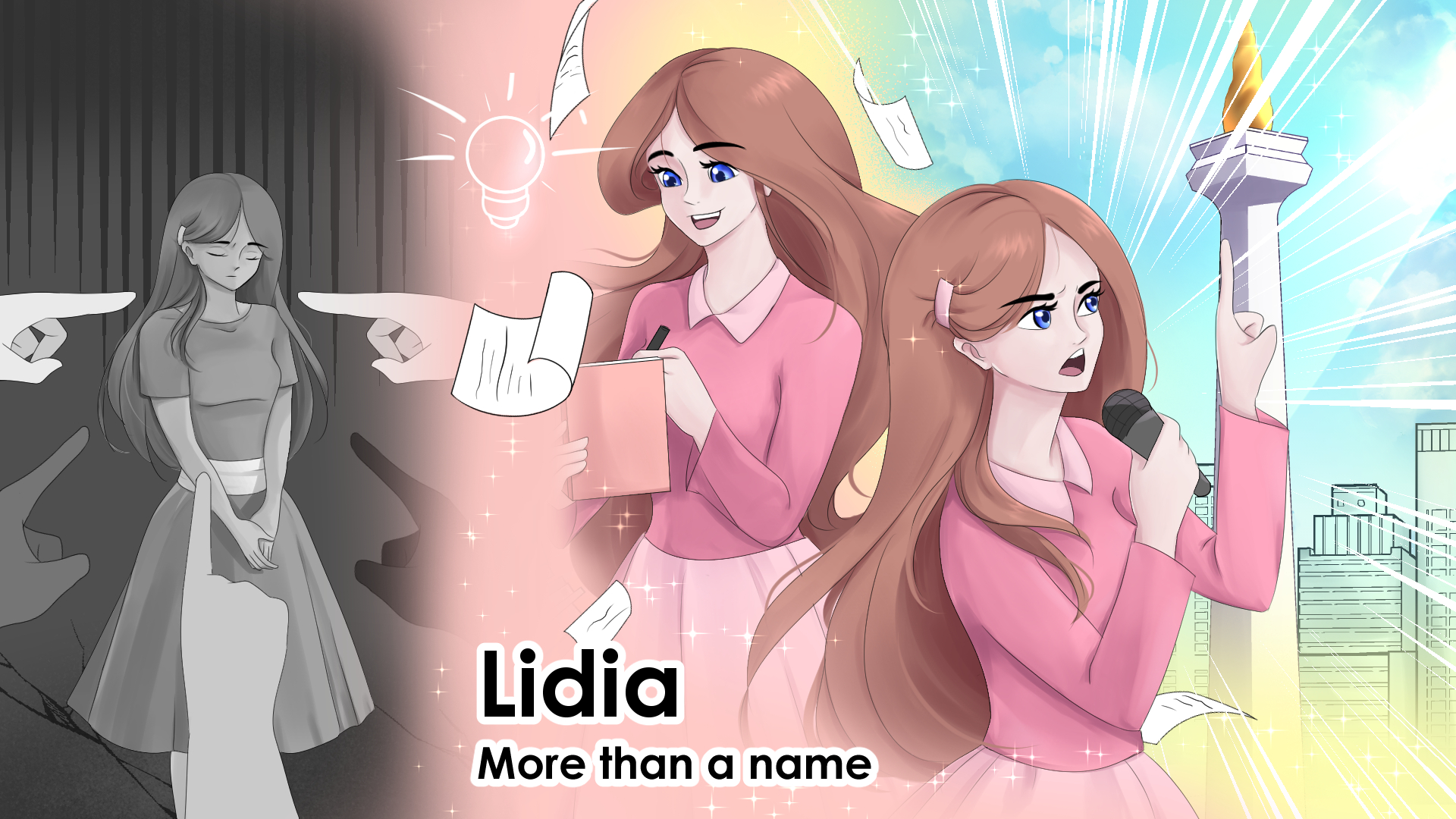

Naming has become a rite of passage throughout human history. My parents named me Lidia, a name taken from the Bible, hoping I would mirror the hospitality of Lidia, a merchant from Thyatira who once opened her home to the Apostle Paul and some of his companions in the Roman city of Philippi.

Until my teenage years, before I really began to think about my identity, mentioning my name was the only thing I could do when people asked me who I was. After graduating high school, I left my hometown of Toraja, South Sulawesi, for Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, to attend college. Moving from my homogeneous habitat to the most diverse area in Indonesia, I became aware that I was so much more than just Lidia. I was a girl with an accent from a working-class family who had to crawl in order to thrive.

I was led to become more than hospitable. I had to labor. Laboring – as hard as it may sound – can be even more difficult when you are anxious about disadvantages like a lack of money. But my determination and my efforts were as wide as the Grand Canyon. I got a scholarship to the United States. The initial plan was to finish a master’s program in pastoral counseling within three years; it was a clinical track program. After one year, I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a psychosocial disability that causes episodes of depression and mania.

My bipolar was so severe that I fell into a psychosis – a break from reality. In the hospital, the nurses took samples of my blood and urine and ran some tests to see if there were other medical conditions contributing to my illness. “There’s nothing wrong, only vitamin D deficiency,” said the psychiatrist. “A lack of vitamin D could affect one’s mood.” Bipolar disorder is often referred to as a mood disorder, though I learned in my healing process that it’s so much more than that. The doctor prescribed a high dose of vitamin D along with other medicines. Never in my life did I think that I would need to consult a doctor about taking vitamin D. Where I come from, I did not have such privilege.

At this point, I imagine you could identify which group(s) I belong to. I am a woman – a gender often seen in Indonesia’s patriarchal society as a second, or inferior, gender. I come from a working-class family. I live with bipolar disorder, which makes me a person with a disability. These are parts of my identity that make me who I am now. Being a woman, coming from a working-class family, and living with a psychosocial disability means I am a triply marginalized identity. My chances for equal work opportunities are limited. The lack of employment opportunities for Indonesians with psychosocial disabilities has been documented by organizations of persons with disabilities (OPDs) like the Indonesian Mental Health Association (IMHA). IMHA often points out how the Indonesian government systematically and structurally discriminates against people with psychosocial disabilities. This discrimination takes the form of what is called “surat keterangan sehat rohani,” or a certificate of spiritual (read: mental) health. This certificate is one of the requirements to apply for a job. The certificate must be issued by a psychiatrist.

My chance to be accepted in a romantic relationship is limited as well. When people learn about my disability, I can see in their faces how surprised they are – how they believe they are facing a person who is less than them, someone not capable of having a family. But again, my determination, spirit, and efforts are vast, so I found a way to heal from this through writing.

A youth-led organization called YIFoS hired me as their book consultant. They want me to interview participants who have been changed by their program, which has three key themes: equality, tolerance, and inclusion. I carry my work well, no less than persons without disabilities. More important, I am able to work well as part of a team. Performing well in my work is a way for me to advocate for myself and other people with disabilities.

When injustices bubble to the surface, I no longer act in a way that society perceives as hospitable. In my neighborhood, people used to make fun of me, saying I was a crazy person living in the area. I told them that a person with disabilities is protected by law and that if they continued, I would call the National Commission on Human Rights. I have learned that one must advocate and be willing to be assertive and vocal, even though in a patriarchal society, these qualities are associated more with men. But again, I am more than my gender and name, and I will not be defined by others.

Lidia Lebang is a mental health advocate with bipolar and anxiety disorders. She has a passion for the intersection of spirituality, psychology/mental health, and activism. She has written three books in Indonesian, and she is currently working on her first book in English, titled The Extended Self: A Diary of An Asian Woman Living with Mental Illnesses.@2023 Lidia Lebang. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

From Isolation to Advocacy

Nigeria’s DeafBlind community has long lacked recognition, but the launch of the Deaf-Blind Inclusive and Advocacy Network marks a turning point. Led by activist Solomon Okelola, the group seeks to address communication barriers and a lack of support. Among those affected is John Shodiya, who once thrived in the Deaf community but struggled with belonging after losing his sight.

Disability Aid Disrupted

The Trump administration’s 90-day pause on USAID funding has had far-reaching consequences, particularly for disabled people and organizations worldwide, including members of the Disability Justice Project (DJP) community. Activists from Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Rwanda report severe disruptions, deepening challenges for marginalized communities, especially disabled people facing conflict, poverty, and structural discrimination.

A Life’s Work

After losing his sight, artist Jean de Dieu Uwikunda found new ways to create, using a flashlight at night to outline objects and distinguishing colors by their scents. His story, along with that of DeafBlind sports coach Jean Marie Furaha, is rare in Rwanda. While over 446,000 Rwandans have disabilities, a 2019 study found that only 52 percent of working-age disabled adults were employed, compared to 71 percent of their non-disabled counterparts.

‘I Won’t Give Up My Rights Anymore’

After a life-altering accident, Lakshmi Lohar struggled with fear and stigma in her rural Nepalese community. In 2023, she found a lifeline through KOSHISH National Mental Health Self-Help Organization, which helped her develop social connections and access vocational training in tailoring. Today, Lakshmi is reclaiming her independence and shaping a future beyond the limitations once placed on her. “I won’t give up my rights anymore,” she says, “just like I learned in the meetings.”

Rwanda’s Marburg Crisis

As Rwanda confronts its first-ever Marburg virus outbreak, people with disabilities face heightened risks — not only from the virus but also from the lack of accessible health information. “Without proper accommodations, such as sign language interpreters, captions, Braille, or visual aids, the Deaf and DeafBlind community may miss crucial information about how to protect themselves, symptoms to watch for, or where to seek help in case of infection,” says Joseph Musabyimana, executive director of the Rwanda Organization of Persons with Deaf Blindness.

Capturing Vision Through Sound and Touch

Last year, the DJP trained Indigenous activists with disabilities from the Pacific on the iPhone camera to create a documentary series on disability and climate change. With VoiceOver, the iPhone provides image descriptions for blind and low-vision filmmakers and offers other accessible features. “If you think about it, it doesn’t make sense for a blind person to use a camera,” says DJP filmmaker Ari Hazelman. “The iPhone gives you more avenues to tell your story in a more profound way as a blind person.”