News

Toward Equitable Health Care

Play audio version

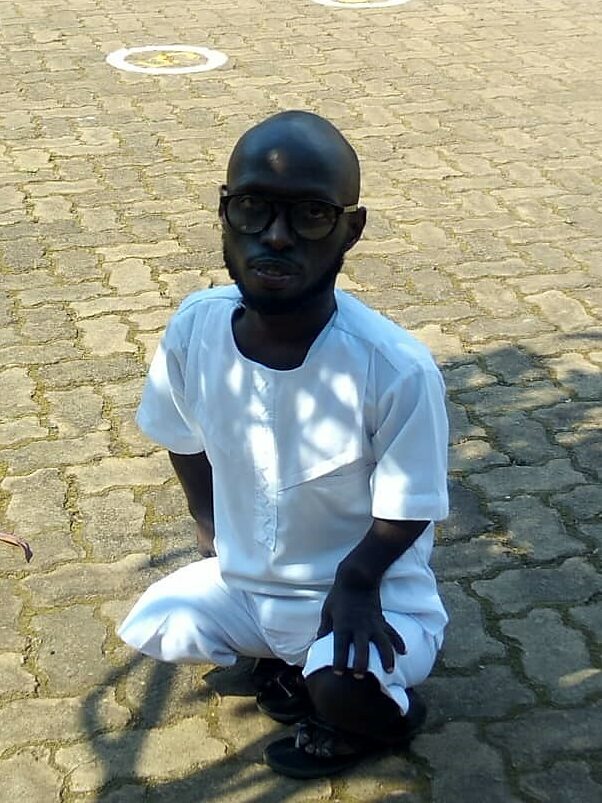

Rwandans with Short Stature Advocate for More Accessible Services, From Lower Reception Windows and Beds to Better Communication

December 14, 2022

KIGALI, Rwanda — Persons with disabilities experience significant barriers to accessing health care, including inaccessible medical clinics and hospitals, a lack of accessible transport options, untrained personnel, inadequate staffing, stigma and discrimination, and inaccessible communication methods and materials. These barriers can be particularly challenging for those residing in rural areas.

Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP) recently conducted an accessibility visit to one local and one regional health center to check on how persons with short stature (also known as persons with dwarfism or little people) could or could not access healthcare services.

“As we know, any person needs healthcare services for any reason, but to persons with short stature, it seems like they are not expected to need such services, as they never access materials and even buildings where they use stairs,” says Appoline Buntubwimana, legal representative at RULP, “and when you ask, they tell you that they never thought of persons with that type of disability. It is rarely finding any post-health center, health center, or even a hospital whose buildings and materials are accessible to persons with short stature in Rwanda.”

During RULP’s visit, staff examined the room where women give birth, checking whether it was accessible for a woman with short stature. Health center officials acknowledged the beds are not accessible – that they are for all women and not specifically for women with short stature. As a result, medical personnel must lift up patients with short stature onto the beds. It is the only way they’ll receive medical attention.

Theodole Niyigaba is a man with short stature who lives in Kigali. He says accessible health services for Rwandans with short stature are nonexistent. Service windows and beds are too high, and patients often must climb steep stairs to access services. “From the introduction of COVID-19 in Rwanda, I have never used any public handwashing station due to their standards. Moreover, in case I need hospital services, like taking medicine, I entered the office instead of waiting at the windows because no one can see me.”

Leonidas Batamugira, director of Remera Health Centre in Kigali, says that although the Rwandan government is trying to help persons with disabilities access services, when it comes to how buildings are constructed and furnished inside, they are still inaccessible to persons with short stature. “Generally, the available chairs, delivery beds, stairs, handwashing facilities, in-patient beds, doors, general chair and tables, we really know that they are not accessible to persons with short stature. Truly, it needs an extra budget that we do not have to have such materials, so we lift her/him up, or else we transfer them to the district hospital for special help,” he says.

Historically, persons with short stature are one of the most marginalized groups in Rwanda. Many have been rejected by their families or bullied by peers, leading to self-isolation and stigma. They have been denied an education, leading to a lack of knowledge about various health conditions and the right people to see when a problem arises. When it comes to healthcare services, they meet physical, material, and communication barriers.

Buntubwimana says persons with short stature are seriously struggling with accessing health care, from reception areas to where they should be receiving services to even who is providing such services. “Many health services like reception, paying for services, and where to take medicine, services are provided through windows which are tall,” she says. “Everyone may imagine what happens when no one is around to help him or her to ask for such services. Sometimes we are served after others or choose to stay home.”

Francine Uwayisaba is a field officer at Rwanda Union of Little People (RULP) and in charge of the organization’s communications. She writes grants, manages RULP’s social media, and composes articles and weekly updates for the website. @2022 RULP. All rights reserved.

News From the Global Frontlines of Disability Justice

Autism, Reframed

Late in life, Malaysian filmmaker Beatrice Leong learned she was autistic and began reckoning with decades of misdiagnosis, harm, and erasure. What started as interviews with other late-diagnosed women became a decision to tell her own story, on her own terms. In The Myth of Monsters, Leong reframes autism through lived experience, using filmmaking as an act of self-definition and political refusal.

Disability and Due Process

As Indonesia overhauls its criminal code, disability rights advocates say long-standing barriers are being reinforced rather than removed. Nena Hutahaean, a lawyer and activist, warns the new code treats disability through a charitable lens rather than as a matter of rights. “Persons with disabilities aren’t supported to be independent and empowered,” she says. “… They’re considered incapable.”

Disability in a Time of War

Ukraine’s long-standing system of institutionalizing children with disabilities has only worsened under the pressures of war. While some facilities received funding to rebuild, children with the highest support needs were left in overcrowded, understaffed institutions where neglect deepened as the conflict escalated. “The war brought incredibly immediate, visceral dangers for this population,” says DRI’s Eric Rosenthal. “Once the war hit, they were immediately left behind.”

The Language Gap

More than a year after the launch of Rwanda’s Sign Language Dictionary, Deaf communities are still waiting for the government to make it official. Without Cabinet recognition, communication in classrooms, hospitals, and courts remains inconsistent. “In the hospital, we still write down symptoms or point to pictures,” says Jannat Umuhoza. “If doctors used sign language from the dictionary, I would feel safe and understood.”

Failure to Inform

Zulaihatu Abdullahi dreamed of finishing school and building a home of her own. But at 19, she died of untreated kidney disease because no one could communicate with her in sign language. Her story reveals how Deaf Nigerian women are often left without lifesaving care. “If only she had access to healthcare where someone could guide her… explain each step, she might still be here,” says Hellen Beyioku-Alase, founder and president of the Deaf Women Aloud Initiative.

Disability in the Crossfire

In Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, ongoing conflict and forced displacement have hit people with disabilities hardest. Rebel groups seized supplies from a clean cooking initiative designed to support displaced people with disabilities, leaving many trapped without aid. “It is still a big difficulty for authorities or government or humanitarian organizations to make a good decision which includes everyone,” says Sylvain Obedi of Enable the Disable Action.